Why Meta shareholders can do little about Mark Zuckerberg

Meta's business performance and Mark Zuckerberg's sacking 11,000 workers are cautionary tales for shareholders, writes UNSW Business School's Mark Humphery-Jenner

“I want to take accountability for these decisions and for how we got here,” tech billionaire Mark Zuckerberg told the 11,000 staff he sacked last week. But does he really?

The retrenchment of about 13 per cent of the workforce at Meta, owner of Facebook and Instagram, comes as Zuckerberg’s ambitions for a “metaverse” tank. The company’s net income in the third quarter of 2022 (July to September) was US$4.4 billion – less than half the US$9.2 billion it made in the same period in 2021.

That’s due to a 5 per cent decline in total revenue and a 20 per cent increase in costs, as the Facebook creator invested in his idea of “an embodied internet – where, instead of just viewing content, you are in it” and readied for a post-COVID boom that never came.

Since he changed the company’s name to Meta a year ago, its stock price has fallen more than 70 per cent, from US$345 to US$101.

Selling is really all the majority of shareholders can do. They are powerless to exert any real influence on Zuckerberg, the company’s chairman and chief executive.

If this had happened to a typical listed company, the chief executive would be under serious pressure from shareholders. But Zuckerberg, who owns about 13.6 per cent of Meta shares, is entrenched due to what is known as a dual-class share structure.

When the company was listed on the NASDAQ tech stock index in 2012, most investors got to buy “class A” shares, with each share being worth one vote at company general meetings. A few investors were issued class B shares, which are not publicly traded and are worth ten votes each.

As of January 2022, there were about 2.3 billion class A shares in Meta, and 412.86 million class B shares. But although class B shares represent just 15 per cent of total stock, they represent 64 per cent of the votes. And it means Zuckerberg alone controls more than 57 per cent of votes – meaning the only way he can be removed as chief executive is if he votes himself out.

Read more: What Meta can learn from the ‘New Coke’ debacle

A trend in tech stocks

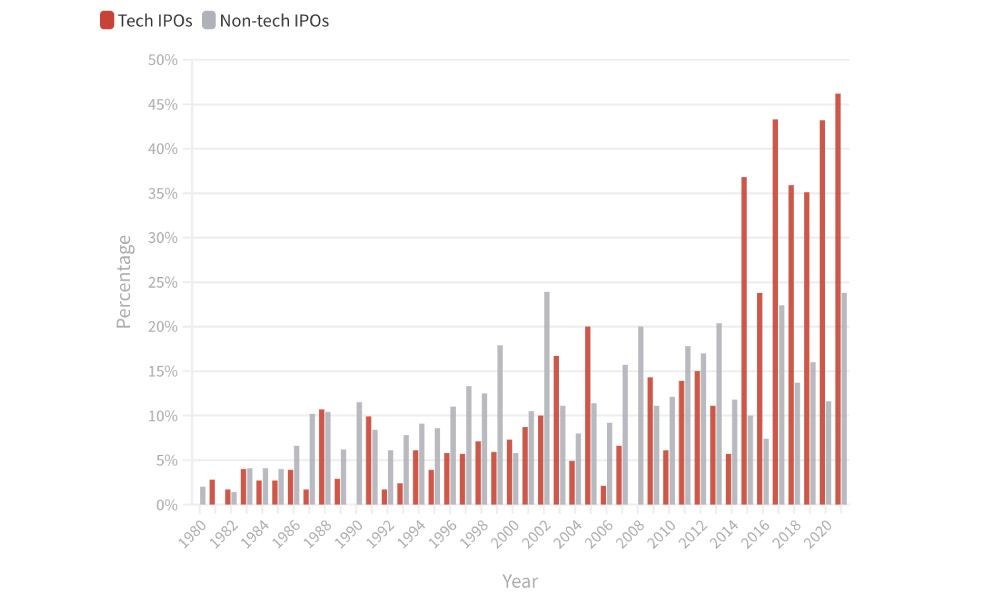

Meta is not the only US company with dual-class shares. Last year almost half of tech companies, and almost a quarter of all companies, that made their initial public offerings (stock exchange listing) issued dual-class shares.

Tech heads love dual-class shares

This is despite considerable evidence of the problems dual-class shares bring – as demonstrated by Meta’s trajectory.

Protection from the usual accountability to shareholders leads to self-interested, complacent and lazy management. Companies with dual-class structures invest less efficiently and make worse takeover decisions but pay their executives more.

Investors cannot vote Zuckerberg out. Their only real option is to sell their shares. Yet despite shares falling 70 per cent in value, Meta’s approach has yet to change.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

It’s a cautionary tale that should signal to investors the risks of investing in such companies – and highlight to policymakers and regulators the danger of allowing dual-class structures.

Mark Humphery-Jenner is an Associate Professor in the School of Banking & Finance at UNSW Business School. He has been published in leading management journals, and his research interests include corporate finance, venture capital and law. For more information, please contact A/Prof. Humphery-Jenner directly. A version of this post first appeared on The Conversation.