A primer on Australian productivity

A slowdown in productivity highlights policy challenges and points to three main areas in need of reform, writes UNSW Business School's Professor Kevin Fox

There has been a lot of productivity growth in Australia. This may sound surprising; the lack of productivity growth is currently an issue of great policy concern and public debate. While it is not obvious from the current focus of public discourse, some industries have had high productivity growth, while others have not.

Knowing just this, a solution to current concerns about productivity growth would seem to be to focus on the poorly performing industries and see what policy settings might improve matters. Unfortunately, it is not quite as simple as this, as even the highly performing industries have had a productivity growth slowdown from around the financial year 2003-2004.

Other industrialised countries are also experiencing productivity growth slowdowns with approximately the same timing. That is, countries that are quite different in terms of their industry structures, red tape, competition policies, tax settings, subsidy schemes to support research and development, and so on, are sharing a similar experience of slower productivity growth from around 2004.

In this context, how do we design appropriate policies that can raise productivity growth and ensure higher living standards for future generations? A focus on three things can help:

- Input growth

- Efficient markets

- Innovation

Before considering these further, it is useful to look at the data to get a sense of what we are dealing with.

Some industries are better than others

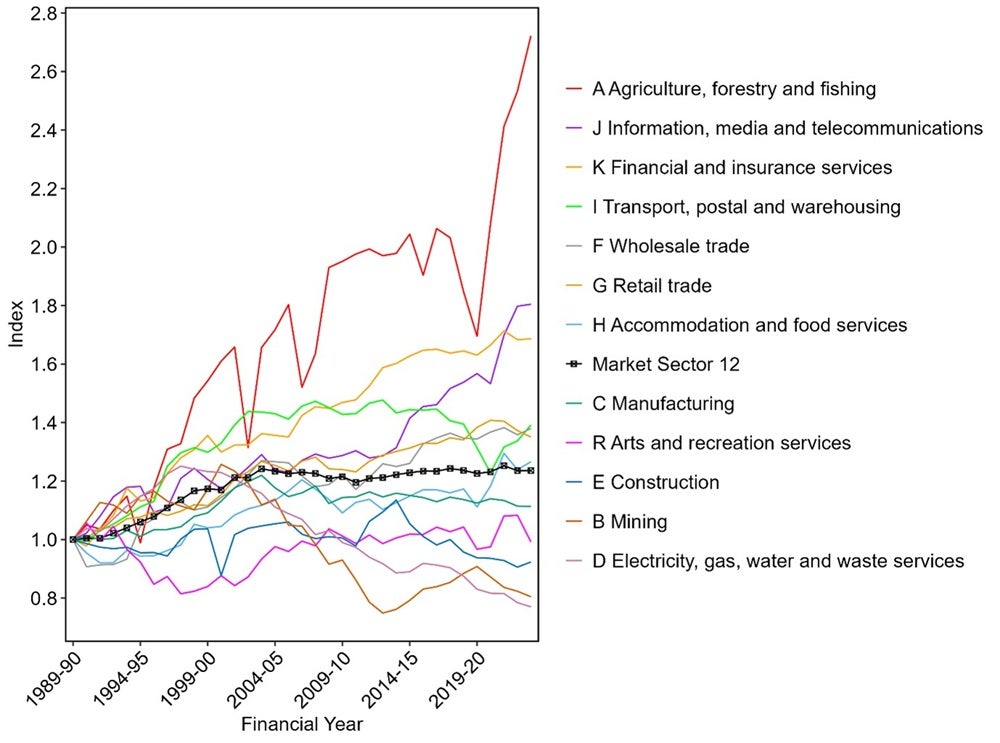

Much public debate on productivity focuses on labour productivity, which is a partial measure of productivity. I focus on the Multifactor Productivity (MFP) growth estimates for the "market sector" produced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The MFP growth estimates are calculated by dividing real value added growth (a measure of output) for the industry by an input index that combines labour and capital. There are twelve industries for which data goes back to 1989-90.

The diverse productivity experience across industries is illustrated in the following figure.

The plotted series are cumulated indices, indicating the level of productivity relative to 1989-90. The productivity performance of the aggregate 12 industry market sectors is represented by the black line with square boxes. We can immediately see from this the reason for the concern about the productivity growth slowdown – while the line was upward sloping prior to 2004-05, it then flattens noticeably, indicating approximately zero productivity growth.

We can also see a huge diversity in performance across the industries within the market sector, with agriculture, forestry and fishing showing quite remarkable relative growth. There are missing inputs that affect the measured performance of this industry. Productivity growth is the growth in output not explained by the growth in inputs. Water is a missing input in almost all productivity analyses, as is the case for these ABS statistics. The disappearance of a non-measured input has no effect on the input index, but it does have an impact on output (e.g. reduced crop yields), reducing measured productivity growth.

The two large downward spikes in 2002-03 and 2006-07 in the productivity level for this industry represent the effects of droughts. The effect of bushfires and floods in 2019-2020 can also be seen. The subsequent dramatic increase in the series is likely due to appropriate amounts of two important unmeasured inputs for agriculture: water and sunshine.

Electricity, gas, water and waste services have had the worst overall performance, with sector productivity being 20% lower in 2024-25 than it was in 1989-90. Contributing factors to this may include network upgrades that avert disruptions in supply but do not result in any more output being produced, and investments in desalination plants that produce little or no output.

Join the conversation: Professor Kevin Fox discusses productivity on LinkedIn

Mining is very profitable, but it too is a poor performer in terms of measured productivity growth. Much of its poor performance can be attributed to the mining investment boom driven by high commodity prices; there was a huge increase in inputs, but with production lags, the output growth does not occur until some years later. (Consistent with international practice, the ABS does not adjust for such lags, as a similar approach would have to be applied to all industries, greatly complicating matters and requiring much more information.) Mine yields have also been falling, due to high commodity prices making otherwise marginal mines profitable. With more input needed to produce an extra unit of output, productivity falls.

Even if we exclude the poorest performing sectors because of peculiarities relating to the measurement of their productivity growth, there is plenty of variety between the high and low performers, but perhaps there is also some commonality of experience.

Productivity growth, but not as we (used to) know it

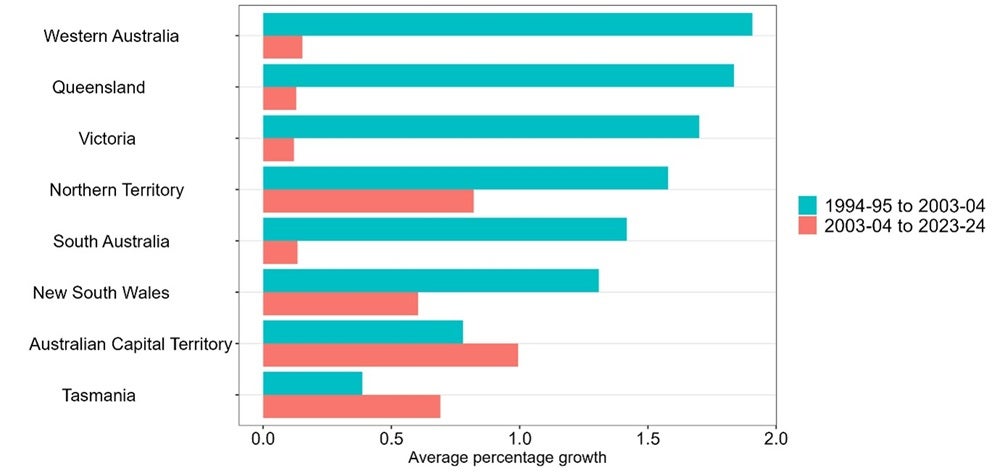

From the following figure, we see that productivity growth has experienced a slowdown across all industries from 2003-04, except for Arts and recreation services, which still exhibited a very low rate of productivity growth in the latter period. That is, while there is huge diversity of industry performance, there is commonality in that all but one industry experienced a productivity slowdown.

There could be mismeasurement at play here. Measurement has become more difficult in the modern economy, especially with the transition towards having a large service sector, where outputs can be hard to measure. However, it is hard to see how mismeasurement suddenly got worse from 2004 to the extent that it could have erased the productivity benefits of technological progress across such a diverse range of industries.

Average multifactor productivity growth by industry division

Is the state of productivity better in some states?

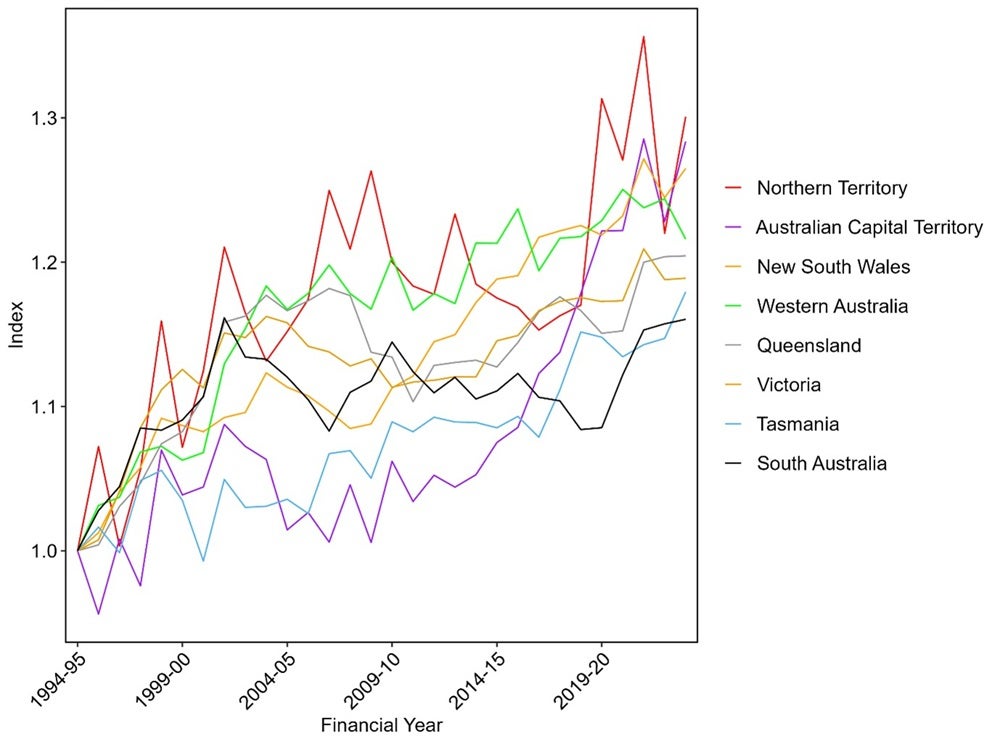

ABS data on the productivity of the states and territories shows a similar pattern as for the industry data – a diversity of performance, but with a slowdown after 2004-05 for all but the ACT and Tasmania. Improved productivity growth in the ACT and Tasmania is welcome, but the growth for both is low in both sub-periods.

The ABS does not publish industry productivity statistics by state and territory, but it is likely that the mining investment boom has impacted on measured productivity of the states of Western Australia, Queensland and the Northern Territory. However, the fall in productivity growth between the sub-periods seems too large to be attributable to a single industry.

Multifactor productivity by state (using hours worked)

Average multifactor productivity growth by state

Three ways to spur productivity

We have a situation where productivity growth has been diverse across industries, but has fallen across all but one after 2003-04, and similarly for the productivity performance across the states and territories. And a similar pattern of decline is seen across very different industrialised economies.

The solution to Australia’s poor productivity performance cannot therefore be to simply address a peculiarly Australian problem, nor can it be to target the performance problems specific to one or two industries.

The problem may seem intractable, but there are three broad areas of focus that can lead to productivity improvements, as follows.

1. Input growth. Policies that are aimed at growing the primary factors of production, labour and capital, can help raise productivity growth. One reason is that there can be increasing economies of scale, such that increasing inputs leads to a more than proportional increase in outputs. There are also benefits from changing the nature of inputs:

- Capital: Incentives to invest in new, better-quality capital can be beneficial, as capital can embody technological progress. Incentives to invest in productive capital are also important. Currently, the returns to investing in housing are very high, attracting investment away from more productive uses.

- Labour: Investment in education and skills can raise the quality of human capital, resulting in a more innovative, adaptable and resilient workforce. Immigration can also be used to address gaps in required skills and keep up with rapid changes in technology.

Learn more: How AI is changing work and boosting economic productivity

2. Efficient markets. Efficient allocation of resources across the economy is important for ensuring society’s resources are put to their best use.

- Competition policy: Well-designed and enforced policies can ensure that monopolists do not capture markets at the expense of access to cheaper and better inputs. They can also stop large firms from controlling segments of the labour market and blocking the entry of new, innovative competitors.

- Flexible labour markets: Job mobility can be improved, ensuring better matching between employees and employers, if there are no non-compete clauses in workers’ contracts and there is national occupational licensing.

3. Innovation. This is what most people think of when contemplating productivity – knowledge creation and transfer, leading to new products and new production processes. This can be assisted by:

- Well-directed support for research and development.

- Supporting university education and research, producing training and knowledge that supports innovative capacity and decision making, and growing the economic competencies of managers.

- Promoting international collaboration to ensure access to the latest research and market developments.

- Removing unnecessary bureaucratic constraints.

- Fostering a dynamic business environment by not propping up failing firms and industries.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

Together, input growth, efficient markets and innovation will promote:

- the diffusion of knowledge and absorption capacity of firms,

- an increase in economic competencies and incentives to make productivity-enhancing decisions,

- and a workforce that can better adjust to rapid structural change.

Finally, a word on artificial intelligence (AI). It is typical that significant new technologies are greeted with both optimism and anxiety – they are either going to usher in a bright new era of prosperity, or they are going to steal our jobs. AI will probably do a bit of both, but not to the extremes that are often suggested. AI, as a general purpose technology, can help raise productivity growth in some sectors of the economy, but it won’t get under the sink and fix my plumbing. Its intrusion into education may result in an AI-dependent, less well-educated workforce, reducing productivity. Hence, it is unlikely that AI by itself is going to solve the problem of slow productivity growth.

Kevin Fox is a Professor in the School of Economics at UNSW Business School, the UK Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (ESCoE), and Director of the Centre for the Applied Economic Research (CAER) at UNSW Business School.