Can Australia pay off its debt without hurting future generations?

The Australian economy faces a fiscal turning point. What do record debt, higher interest rates, tighter liquidity, and low productivity mean for future generations?

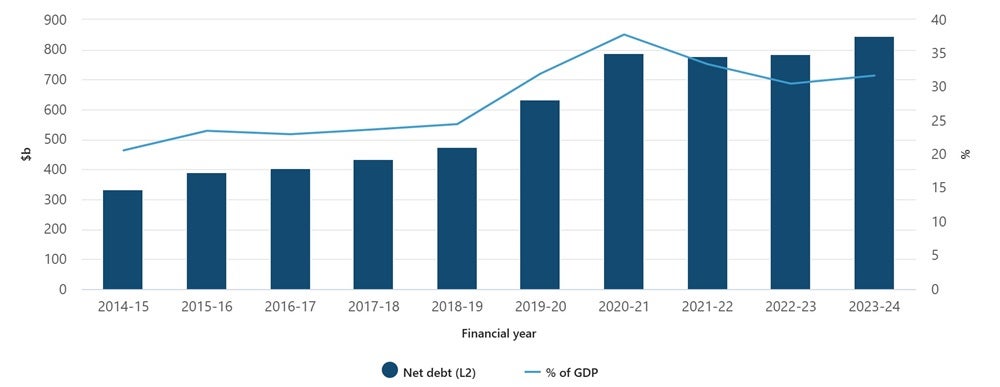

Australia is set to end the 2025 financial year with gross debt at around $1.02 trillion (35.5 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP)), according to Australian government budget papers. Debt as a percentage of GDP measures how much a country owes compared to the size of its economy. If this ratio climbs too high, it can signal fiscal stress, reduce investor confidence, and increase the cost of government borrowing.

Australia’s net debt is also forecast to increase significantly to $1.22 trillion (36.8 per cent of GDP) in 2028-29, with the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) emphasising challenges around managing liquidity and credit rating. While high public debt doesn’t automatically spark a crisis, it does underscore the long-term risks of unchecked liabilities and rising interest payments.

A recent report, Five Economic Themes That Will Dominate the Next Parliament, jointly published by the e61 Institute and UNSW Sydney, found that governments must implement critical policy priorities to ensure that Australia’s debt helps, not hinders, future generations. Australia’s leading economics experts, including e61 CEO Michael Brennan, Former RBA Governor and UNSW Sydney alumnus Philip Lowe, and UNSW Business School Scientia Professor of Economics Richard Holden, recently sat down to discuss why Australia’s rising debt levels shouldn’t be ignored.

Australia’s new fiscal reality: Interest rates rising, growth slowing

The experts explained that the Australian government debt trajectory is manageable, but only with immediate, disciplined action. Avoiding hard decisions today could severely limit future fiscal choices, as liabilities compound and net debt escalates. Prof. Holden, Mr Brennan, and Mr Lowe agreed that debt levels represent political choices that will drive Australia’s future.

Prof. Holden said: “If we pay some rate of interest on our existing national debt, let's call it R, and if our national income grows at G, there’s historical evidence that growth has sometimes been higher than what we pay on the debt. G is bigger than R. At that point, you don't need to worry too much about debt. Is that right?”

Australian government net debt as a percentage of GDP

Mr Lowe, former Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), acknowledged that historically this was the case, with growth in GDP comfortably exceeding interest payments on government securities, enabling manageable repayments without substantial government borrowing. However, he warned that this scenario has fundamentally changed following the pandemic and no longer holds true.

Mr Lowe explained: “For most periods since World War II, the nominal growth rate of the economy has been higher than the average interest rates that the government paid on the debt. For 40 or 50 years, debt ratios came down without governments having to do too much hard work because nominal growth was greater than the interest rate. I don't think we're going to be in that situation anymore.

“Real growth has slowed because productivity growth has slowed, and inflation is now back to low levels. Nominal growth is back to fairly low levels, and real interest rates are probably going to be a bit higher because governments around the world have had a deterioration in fiscal position. We can't rely on that favourable configuration in the future. We've got to make sure the primary budget balance is in balance.”

This means Australia's public debt faces increased pressure from higher interest rates, rising budget deficits, and the need for careful management of investment priorities, including government spending on green energy transitions.

Productivity: not a silver bullet, but essential

Australia’s productivity – a measure of how efficiently resources are used to produce goods or services – has slowed. Labour productivity rose to a record high from the onset of the pandemic in January 2020 to March 2022 before declining and returning to its pre-pandemic level in June 2023.

Mr Brennan, economist and CEO of the e61 Policy Institute, emphasised the importance of accepting that productivity is low. And because of this, the general government sector must acknowledge that Australia can't simply “outgrow” its public debt. Instead, the Australian government must create fiscal frameworks accounting for realistic productivity growth scenarios and tighter financial assets management.

“I think one of the things we have to grapple with is, what does fiscal policy have to look like if we just accept that productivity growth will be lower? That's not to be defeatist, but I think we need fiscal frameworks that allow for that, not provide an easy fantasy that we can grow our way out of any level of debt or deficit.

“But there are things we can do to raise the growth rate. One of the things that doesn't lift your per capita growth rate but does lift your growth rate for the purposes of debt sustainability is population growth. To the extent that we have a rapidly rising population, immigrants coming to the country are partly sharing that liability, but it's worthwhile for them because the present value of the opportunities is still very, very good.”

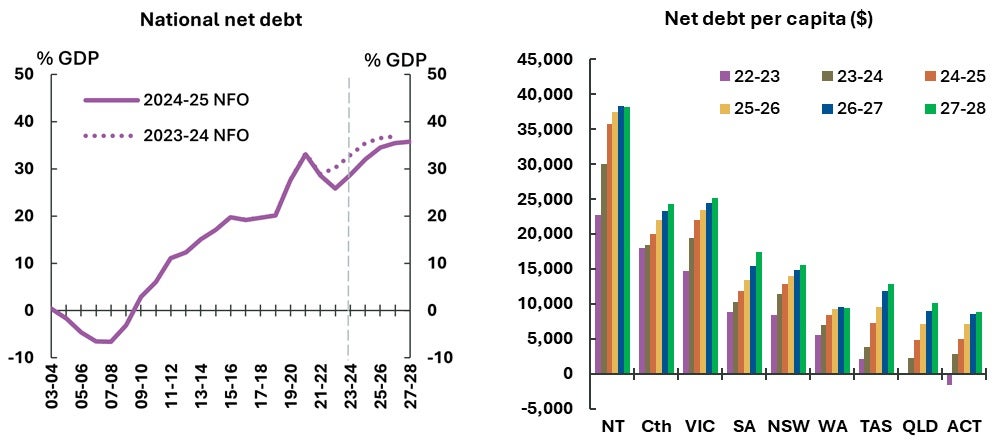

The Australian economy isn't just impacted federally but also at the state level. Mr Brennan explained: “The NSW Budget projected a surplus in 2019-20, and then the pandemic came along and all fell apart. It's never been back in surplus since, and now it's projected not to return to surplus for another few years, so we'll have the better part of a decade of deficit as a result of the pandemic.

“That doesn't feel quite right, and part of the reason for that is not because they're still spending on pandemic-related things. It's really difficult as an elected government, as Phil says, to preside over a fiscal consolidation.”

Mr Brennan labelled state government financial pressures as "the canary in the coal mine," facing rising liabilities, lower financial assets relative to obligations, and higher exposure to interest payments. "The cost base for states rises faster than their revenue base," Mr Brennan said, highlighting that state general government sectors primarily employ people and own assets, contrasting with the federal budget's flexibility. This means state debt levels are less responsive to economic cycles.

Professor Holden noted that Australia's recent experience of "seven consecutive quarters of negative GDP per capita growth" challenges traditional definitions of recession, highlighting deeper economic stagnation that may be masked by high population growth. He suggested that redefining a recession to include per capita measures or adopting a more holistic approach, similar to that used by America's National Bureau of Economic Research, could impose greater discipline on government spending and encourage better economic policy decisions.

In agreement, Mr Lowe emphasised that Australia requires clearer political narratives around productivity and investment. He suggested politicians frame necessary reforms explicitly as measures "for the sake of our kids," to build public support and secure long-term economic growth.

Debt management: How should Australia respond?

While the Australian government issues debt securities such as government bonds to finance deficits, sustained budget surpluses and prudent management of national savings vehicles like the Future Fund will be essential to stabilise long-term debt. For example, Mr Lowe suggested that states will require a new revenue base, recommended a generalised land tax, and urged clarity on the levels of government spending responsibilities.

He said: “The states spend as much time squabbling amongst one another about the share of the federal pie as actually working on positive reforms. People have been struggling for decades with how to ensure the states' revenue base matches their growing expenditure needs.

“I think a generalised land tax is the best new revenue base, but they also need some agreement with the federal government on funding services. It's fundamentally a difficult issue and has been since Federation.”

In short, to ensure debt sustainability, the experts suggested several key strategies:

- Strengthening federal and state fiscal frameworks to better balance government borrowing and repayments.

- Enhancing productivity and per capita GDP growth through credible regulation, innovation incentives, and investment in education and research and development.

- Clarifying responsibilities and revenue arrangements between federal and state general government sectors, perhaps via improved land tax systems.

- Governments need to adopt more compelling narratives, like investing for the sake of future generations, to build public trust and support for responsible, long-term fiscal reform.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

While the experts confirmed Australia's gross debt isn't an immediate financial crisis, neglecting it could lead to severe future consequences. The public sector, informed by insights from the RBA and IMF benchmarks, must proactively manage balance sheet risks to safeguard Australia's credit rating.

Mr Lowe summarised succinctly: "We’ve got to invest more and we've got to push the boundaries so our kids can have a better lifestyle than we do."