Is Victoria the canary in Australia’s debt coalmine?

Victoria’s rapidly rising state debt, downgraded credit rating and cost blowouts signal deep structural problems with the state's economy and fiscal management

Victoria stands at the precipice of a fiscal crisis. With net debt projected to reach $187 billion by 2028 and a credit rating already downgraded to AA – the lowest of any Australian state – the Victorian government faces serious questions about its economic future. The numbers paint a picture of financial distress: debt has grown by 415% since 2014, while the economy expanded by just 29%. Interest payments are forecast to rise by 40% over the next four years, and household income per capita was the second lowest in the nation in 2023-2024.

The woeful economic tale of Victoria is not just one of poor fiscal management, but deeper structural problems in how Australian states evaluate major projects, manage public sector growth, and respond to crises, according to Professor Gigi Foster from the School of Economics at UNSW Business School.

Public sector growth outpaces private innovation

Victoria's public service has expanded by 59% over the past 15 years, while the population has grown by just 29%. The wage bill explosion – 152% over the same period – represents the largest increase in the nation. Prof. Foster identified this imbalance as a threat to the state's economic position.

"The private sector is, in general, both more efficient and more innovative than the public sector (despite a few 'big wins' for public-sector innovation over the years, often driven by military objectives), both of which are because of the lack of competition in the public sector," Prof. Foster noted. She explained that competitive pressure, present in the private sector but absent or minimal in the government, is the most effective mechanism to stimulate efficient resource use and drive innovation.

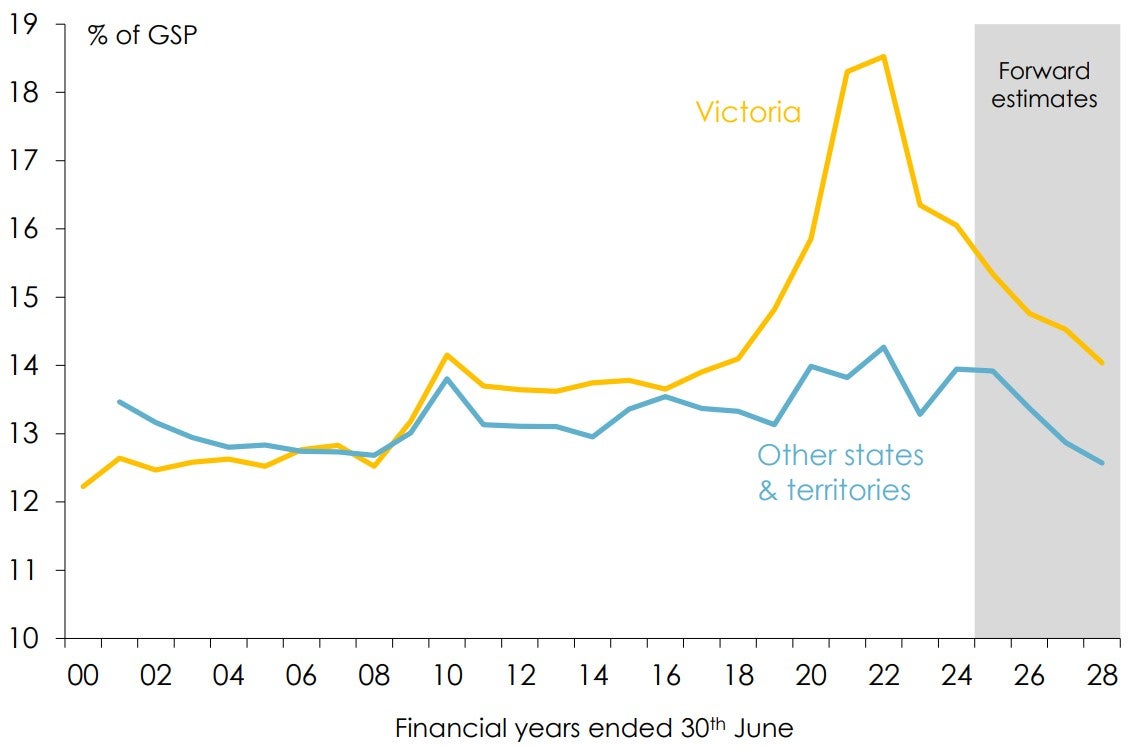

General government operating expenses, Victoria vs other states and territories

The consequences extended beyond simple inefficiency. Prof. Foster argued that the public sector expansion masked deeper economic problems while creating unhealthy dependencies. "Having an imbalance of the size we see in new job growth in the public vs private sector simultaneously conceals stagnating private-sector growth, makes more Victorians directly dependent upon the government, and contributes to the productivity stagnation that has afflicted Australia for years."

Employee costs consumed nearly 40% of the Victorian budget, compared to just 5% for the federal government. Every Victorian budget since 2015-16 projected modest growth in employee expenses of around 3.2% annually, yet actual growth exceeded 7%.

Victoria's general government expenses

The $200 billion infrastructure gamble that failed basic economic tests

The Suburban Rail Loop emerged as the centrepiece of Victoria's infrastructure programme, representing a $200 billion commitment that would shape the state's finances for generations. Instead, Prof. Foster said it has been a fundamental failure in project evaluation methodology.

"The standard tool for evaluating a government policy, including a policy to invest in a large infrastructure project, is cost-benefit analysis – the same type of analysis I engaged in to demonstrate conclusively that covid lockdowns were a disastrous policy choice," Prof. Foster explained. The Victorian government's business case for the project showed benefit-cost ratios that infrastructure experts questioned, with leaked modelling revealing the line would carry just 24,000 trips daily between its first two stations by mid-century, when Melbourne's population would reach 8 million.

Prof. Foster suggested the project's approval process involved more than just flawed economics. "It would not surprise me in the slightest if the Victorian project involved benefits flowing to long-term acquaintances and business representatives well-known to Victorian government officials,” said Prof. Foster, who said this was likely based on cronyism and the well-known pattern of how politicians abuse their positions of power for their own gain.

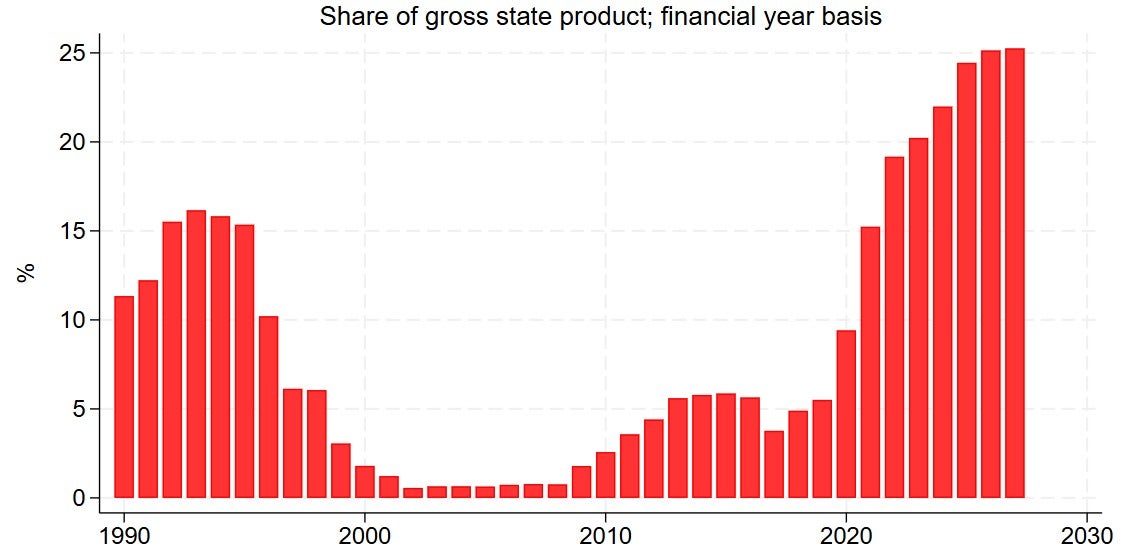

The contrast with historical spending patterns is stark. For 25 years from 1990, Victorian governments invested roughly 1% of Gross State Product annually in capital works. After 2016-17, this figure ballooned to over 2.5%, a level the e61 Institute described as beyond the economy's capacity to absorb. Cost overruns became the norm rather than the exception, with the North East Link blowing out by more than $10 billion to $26.1 billion and the Metro Rail Tunnel adding $837 million to reach $13.48 billion.

Victoria – contributions to general government net cash flow

Tax burden drives business and talent away

Victoria maintains 33 separate taxes, levies, and duties, with property owners facing 13 different imposts on ownership, investment, and transactions. The COVID-19 debt levy, introduced as a temporary measure, was scheduled to run until 2033, affecting even modest landholdings with a value above $50,000.

Prof. Foster's assessment was blunt: "One need not look up anything further to conclude from the numbers that Victoria's tax burden is not good for business or individuals."

The evidence of capital and talent flight emerged in migration patterns. Australian Bureau of Statistics data shows Victoria experienced a net interstate migration loss of 15,847 people in 2023-24, the worst result among all states. Queensland gained 34,788 interstate migrants in the same period, while Western Australia attracted 11,492. The pattern continued into 2025, with data suggesting an acceleration of the exodus.

Learn more: Can Australia pay off its debt without hurting future generations?

Business relocations followed similar patterns, with the Australian Bureau of Statistics confirming high numbers of Victorian businesses closing or relocating interstate. Meanwhile, the Business Council of Australia has stated that Victoria is the worst place in the country for business, citing excessive government taxes and regulations.

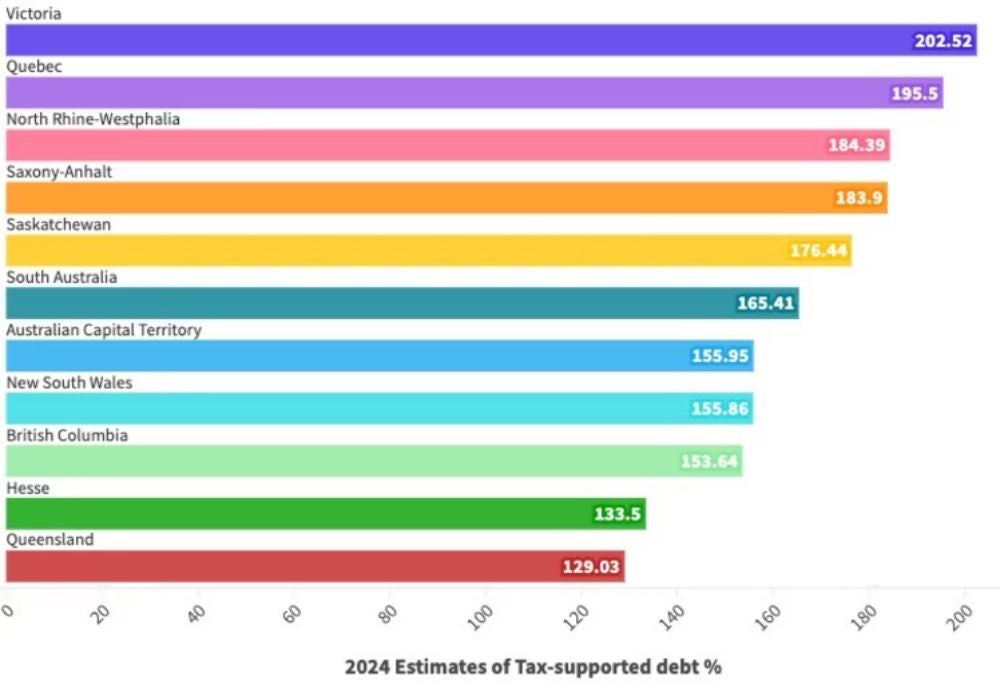

Credit downgrades threaten investment future

S&P Global Ratings warned Victoria faced another downgrade to AA- if state debt reached 240% of operating revenues or if interest payments exceeded 10% of revenues. With a debt-to-revenue ratio of 214% (and trending upward), the state is approaching these triggers rapidly.

Prof. Foster outlined the implications of further downgrades for Victoria's economic prospects. "I cannot predict exactly what the economic fallout will be from a debt downgrade, but in general, it means that investors should be expected to become less confident in the ability of the debtor (i.e., Victoria) to repay,” she said. “This means that fewer investors are likely to invest in the state, and that more regulatory promises, tax breaks, or other special provisions will be required in order to lure them to invest."

She emphasised the fundamental role of investment in economic progress. "Investment is a major ultimate source of increases in human living standards – so this should be expected to hurt Victorians."

With the Treasury Corporation of Victoria estimating $86 billion in debt requiring refinancing between 2029 and 2034 at rates potentially double those secured during the pandemic, the interest burden is likely to consume an ever-growing share of state revenue.

Household incomes bear the burden of debt

Victorian households experienced a significant decline in household income per capita, which was 10% below the national average in 2023-24, the second lowest in the nation. Prof. Foster explained the mechanism linking government debt to declines in living.

"More government debt means more need to pay it back in future years, and these payback amounts are then NOT used to invest in areas that would make Victorians better off – whether that be job placement programmes, apprenticeship training subsidies, healthcare investments, or whatever else (all of which, in different ways, help to support household income growth)," she said. "That is the main problem with having a lot of debt: it crowds out other forms of government investment."

Prof. Foster made the important distinction between productive and unproductive debt. "Now, if Victoria had gone into debt in order to finance its own future productivity growth, then one could argue that the debt was not so bad, since its payback could be financed by the excess returns in future years produced directly by whatever productivity-enhancing investments the debt was used to pay for in the first period."

Her assessment of Victoria's borrowing proved damning. "Sadly, in the case of Victoria's debt, this is not the main line item that the present debt was initially used to pay for."

Victoria government general net debt

COVID policies accelerated the debt crisis

Victoria endured one of the longest lockdowns globally, exceeding 260 days of restrictions. The state's approach to pandemic management left lasting fiscal scars, according to Prof. Foster, who attributed much of the current crisis directly to these policy choices.

"Much of Victoria's debt is because of its anti-social, anti-human covid policy choices – not just the lockdowns but the associated government handouts used to keep people and businesses afloat while their government took away their rights and their livelihoods," Prof. Foster stated. "A recent IPA report provides more detailed information on what happened in Victoria during covid and how much debt was accumulated due to COVID policies, which I also discuss in my first and second co-authored covid-era books."

The e61 Institute estimated that perhaps $75 billion of the debt increase since 2019 could be attributed to COVID-related spending. However, this still left approximately $50 billion in additional borrowing unrelated to the pandemic, suggesting deeper structural problems predated the crisis.

Governance reform beyond debt rules

When asked about fiscal rules or constitutional amendments other states might adopt to avoid Victoria's fate, Prof. Foster argued for more fundamental changes than mechanical debt limits.

"We need not merely a rethink of rules around debt accumulation (which inevitably will be tossed out or worked around expertly in future if the incentives of those in authority are strongly enough served by not adhering to them), but a massive overhaul of our governance and other systems in Australia," Prof. Foster asserted.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

She identified a disconnect between political decision-making and public interest. "At the moment, an out-of-touch elite routinely selects policies that run roughshod over the actual interests of the Australian people – and this is particularly in evidence in Victoria."

International examples generally support this view. For example, while Germany's constitutional debt brake initially constrained borrowing, governments found ways to circumvent restrictions when politically expedient. Switzerland's debt brake proved more robust, but operated within a different federal structure and political culture. Lessons from abroad suggest that rules alone cannot substitute for political will and accountability.

Key takeaways for Australia

Victoria's experience, detailed in a comprehensive analysis by the Victorian Auditor-General's Office and S&P Global's subnational debt reports, demonstrates that fiscal crises can develop gradually or suddenly, sometimes in sequence. Other Australian states should take the opportunity to learn from Victoria's mistakes, but only if they act before similar dynamics become entrenched.

States with the highest amount of subnational debt around the world

Prof. Foster suggested a few guidelines to inform reform directions. “First, bear in mind that some problems – in fact, many problems – are more effectively resolved locally than at a higher level of authority (this is the essence of the principle of subsidiarity), while at the moment our public sector is very large by historical standards,” she said.

“This means that the most beneficial type of action to address modern problems is often to reduce government activity, loosen regulations, or downsize a government department, liberating private-sector and local solutions.

“Second, the wider the gap between the needs of the people and the focus of a government, the sicker is our democracy. So, good-hearted public servants should seek ways to revive democratic voice – whether through state-wide referenda, citizen juries, personnel rotation (to prevent the development of networks of favouritism), or in other ways. Governance guided by these two broad principles can help deliver better results for Australia’s people at lower cost.”