Beyond subscription models: recurring revenue-generating patterns

With Netflix’s loss of subscribers, it may be time to move towards alternative models of customer retention, write Alexander Osterwalder and Matthieu Manzoni

This article is republished with permission from I by IMD, the knowledge platform of IMD Business School. You may access the original article here.

Over the last decade, subscription-based businesses have grown more than five times faster than the S&P 500. Understandably, this growth has led business leaders to try to fit a subscription model into their business. This is perhaps even more so after the pandemic, with customers having experienced subscription models in new areas (such as Hello Fresh’s meal boxes) and the increased penetration of established subscription models – exemplified by Netflix gaining a record 37 million paid memberships in 2020. However, in the wake of Netflix losing $50 billion in market cap following its first loss of customers in more than a decade, it’s becoming clear that subscriptions are not infallible.

When reading the examples of successful businesses generating recurring revenue without a subscription model, don’t conceptualise them as individual cases. Instead, look past the specifics to understand the pattern the business relies on and determine if that pattern might be adaptable to your arena. Companies like Apple and Microsoft have been hugely successful in locking in customers and creating recurring revenue in other ways which may be more relevant to your business.

The subscription hype

When looking at massively successful businesses, leaders and observers tend to look too closely at the specifics to draw inspiration from the approach these businesses took. Rather than seeing the whole picture, they focus on the tip of the iceberg.

Due to their overwhelming success, subscription models are increasingly considered an end rather than a means. A 2021 McKinsey article perfectly exemplifies this trend: the article focuses entirely on how to force fit a subscription model onto a business, rather than zooming out on what should be the overarching objective; enabling a business to generate recurring revenue.

One of the reasons why subscription models are interesting is because they create gravity – or stickiness – as it requires effort for the customer to switch to another product or brand. But while subscription models are great at consistently billing customers, they only work up to a certain point – after all, it takes just a few minutes to unsubscribe. While some subscription models do boast impressive retention rate in the short term (with Spotify showing an impressive 63 per cent retention rate on premium accounts after 12 months) they exhibit little real stickiness. If a new and more appealing music service was launched tomorrow, there would be nothing tying customers to Spotify, leading the brand to suffer from the same downturn in subscribers as Netflix.

Gravity creators and resource castles

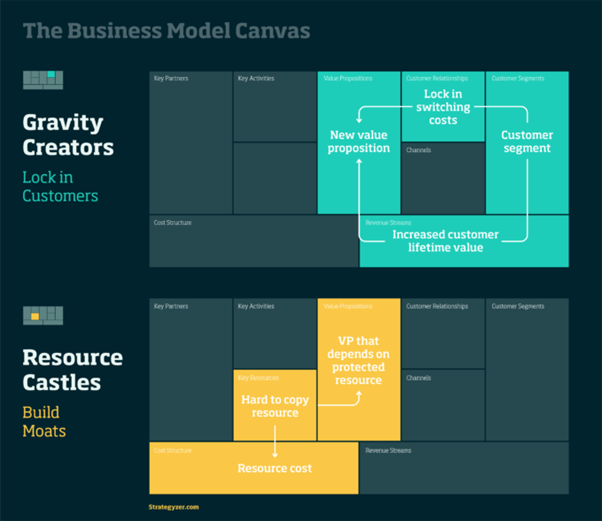

Looking at some of the most successful businesses of the past century, we identified two alternative patterns that enabled the generation of recurring revenue without the use of subscription models. We call these patterns the Gravity Creator and the Resource Castle. The companies we looked at found novel ways to leverage these patterns, and successfully adapted them to their arenas. With the use of the Business Model Canvas below, we can visualise how these two business model patterns differ from one another – and how they generate value for customers.

From video games to silicon chips, companies such as Nintendo and ARM have successfully used these patterns to increase customer lifetime value and generate recurring revenue. Often overlooked in favour of subscription models, these patterns remain largely unused by many industries. Company leaders from all fields should pause to consider if these patterns might work better for their business.

Lock in your customers with high switching costs: the Apple success story

There are alternative ways for companies to create gravity. The first is with the creation of switching costs, which make it unpleasant for customers to switch products, while also making it interesting for them to remain customers.

Over the last 30 years, Apple has arguably been one of the major drivers behind the new era of digital connectivity. The tech giant’s uncanny ability to retain customers during this period was largely based on its leveraging of the high switching costs it created around the “1000 songs in your pocket” value proposition for the first gen iPod in 2001. While the original buy-to-own model used by iTunes was less profitable than the hardware, founder Steve Jobs realised that by locking customers’ music library onto Apple products it would lock customers into the broader Apple ecosystem.

People first bought the iPod – which was miles ahead of other MP3 players on the market in terms of its size and storage capability – then went on to spend hundreds of dollars building their iTunes libraries. Those libraries could not be transferred to any other hardware, so when it came time to buy a new phone or a new laptop, customers gravitated towards the hardware that enabled them to most easily leverage their investment: Apple products. It’s the perfect example of gravity.

Read more: How Spotify is leading the music streaming revolution

Today, the value proposition that retains customers has shifted away from iTunes towards the Apple ecosystem and brand loyalty. This isn’t to say that Apple has abandoned the idea of automatically recurring sales. Users now pay monthly fees for services like iCloud and Apple Music, and the company is considering implementing a subscription model for all new iPhones. But to establish its customer base, it first focused on locking in customers by engineering high switching costs.

Using this overwhelming early success, Apple became omnipresent in the consumer electronics space, using the network effects that its ecosystem of co-dependent products generated (needing a MacBook to leverage the full capabilities of an iPad, for example). This omnipresence made Apple the brand that Millennials are most attached to. This attachment – combined with serious work on the part of Apple to retain this position – translates into a significantly higher NPS score than any other consumer electronics company, with Apple boasting an astounding score of 72. The industry average is 41. This attachment and brand loyalty is yet another representation of the gravity that Apple managed to create to retain its customers.

Importantly, this gravity is not perceived as a hindrance by customers, but rather as a component of the value proposition. Apple has created significant advantages to staying in their product ecosystem: the interconnectedness of their devices was revolutionary when it first came out, and the ease of use of their devices remains unparalleled, with new settings like the ability to copy text on your iPhone and instantly paste it on your MacBook consistently coming out. While this might seem like a rather basic concept, it is an incredibly important one: can you create incentives for customers to remain in your ecosystem and purchase more of your products?

Today Apple remains the largest player in the US cellphone market (with more than 52 per cent market share in 2021) and is battling Samsung for the worldwide leader position – winning out that battle in Q4 of 2021.

Historical gravity creators

Another interesting, and perhaps surprising, example of this pattern is the textbook industry. Historically, once a school or school board adopted a particular biology textbook for instance, the likelihood that the board would then switch to a different textbook is low, simply because designing a new syllabus around a new textbook is a lot of work. This enables a publishing house to publish new editions at very little additional cost and sell them to schools, creating recurring revenue. This led publishing houses like McGraw-Hill and Wiley to have very high profit margins (25 per cent and 15 per cent respectively).

The “consumable” nature of textbooks historically further reinforced the need for new purchases. Once the books had been given to a cohort of students or had been used past the point of being able to be passed on, another batch had to be purchased, further reinforcing the generation of recurring revenue. If you’ve ever wondered why almost all textbooks were fragile paperbacks, you have just stumbled across one of the answers. With the rise of digital textbooks, this trend did not go away. Schools and universities continue to have to buy licenses of textbooks for their students, and with each new edition of the textbook that is published comes a new wave of revenue for the publisher as the switching costs of redesigning a syllabus around a new textbook remain burdensome.

While this rise in digital textbooks has of course dampened the effects of this pattern, it hasn’t rendered it obsolete by any means. It also enabled the industry to leverage it to benefit from absurd price increases over the last 30 years (a whopping 800 per cent, compared to 250 per cent for consumer prices).

Read more: Can you turn a profit in the new news landscape?

Lock in your customers with an affordable investment

The second way to create gravity is with the use of an installed base, where an upfront investment leads to subsequent purchases (think printers and brand-specific ink cartridges).

Microsoft’s transformation of computing – getting computer manufacturers to preinstall Windows on their computers – is one of its two recurring revenue-generating machines. In 2001, in response to the record-breaking number of sales of Sony’s PlayStation 2, Microsoft created the Xbox. To encourage mass adoption, Microsoft subsidised the price of the technologically superior console. In doing so, they built a large base of customers now eager to buy games for their consoles.

Meeting this demand, Microsoft sold its own games – including the Halo franchise, which has generated an astounding $5 billion over the past 20 years – and received royalties from the sale of third-party games. This combination of transactional and recurring revenue generated by royalties created a very stable and powerful business model. Better even, this pattern was self-reinforcing. Microsoft was able to leverage its user base into creating new versions of the console, selling even more games.

Another example of this pattern is the Nintendo Wii. Unlike the Xbox, the Wii relied on inferior technology – off-the-shelf, motion-sensing technology. While other video game makers were locked in an arms race to create a technologically superior console for “hardcore gamers,” Nintendo used cheaper technology to cater to a larger audience: “casual gamers.” The cheaper console that promised a fun and an engaging experience appealed to a wider audience. Nintendo quickly sold a lot of units and, crucially, turned a profit on each console – unlike Microsoft, which only earned revenue through games. This new pool of Wii consumers then needed to buy games, creating recurring revenue.

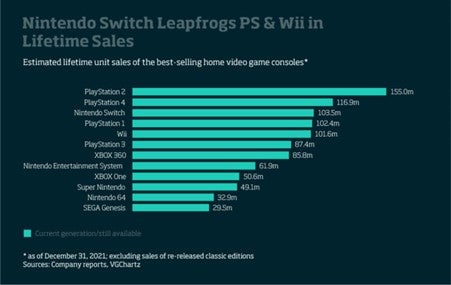

The diagram below shows just how successful this approach was, as the Wii became Nintendo’s highest-selling console ever (until it was recently overtaken by the Nintendo Switch, a console that similarly leverages the casual gamer demographic) outselling Microsoft’s best-selling console by more than 15 million units.

Beyond the differing successes of Microsoft and Nintendo, it’s important to remember why these examples are interesting. By creating an affordable product necessary to the consumption of their recurring revenue-generating product, these companies locked in their customers in a more secure fashion than they would have had if they used a subscription model. Switching from the Xbox to the PlayStation requires you to abandon your gaming catalogue and buy a new console, whereas you can switch from Netflix to Disney+ in a matter of seconds without buying a new TV.

This is the same pattern that Nespresso, Gillette and Kodak used to gain massive market shares – they don’t rely on a subscription to generate recurring revenue, but rather this installed base element where customers lock themselves in with their first purchase.

Resource Castle

Owning key resources that are difficult or impossible to copy – we call these Resource Castles – can create a significant competitive advantage for firms, enabling them to price and package their goods differently. Resource Castles can take many shapes, from User-Base to Platform and IP, and can generate recurring revenue by leveraging their hard-to-copy resource. Google’s impossibly large user base, for instance, forces marketers to bid on ad words every month, and Netflix’s extensive catalog (its IP) gets customers to pay its monthly subscription fee. These companies then spend huge amounts to retain that advantage – whether by creating new IP (as Netflix does) or by continuing to improve their product (as Google does).

This pattern of reinvestment to maintain value is precisely what makes subscription models so difficult to implement. We outline a pattern below that removes that barrier while leveraging the strengths of an IP Castle.

Read more: Fuse soft skills and digital for customer centricity on steroids

Build an IP Castle – without falling into the subscription trap

You may not have heard of ARM and its silicon chips, but you likely have a phone that relies on its technology. ARM licenses its intellectual property to consumer electronics companies including Samsung, Apple, and Microsoft for an upfront fee. It then also receives recurring royalties from the sale of products that use its chips, generating both transactional and recurring revenue. What makes this model and underlying pattern particularly effective is what they do next.

ARM re-invests in R&D – which it did to the tune of 42 per cent of its revenues in 2018 – to later license the new and upgraded version of the chip to those same consumer electronics companies. Rather than handing over access to all their IP for a subscription fee, ARM leverages the competitive market of consumer electronics which requires companies to have the latest chip technology.

In so doing, ARM receives new licensing fees each time it comes out with a new chip. In a way, this is a sort of transactional recurring revenue – while companies do not pay it automatically as they would with a subscription fee, they must pay it to remain competitive in the market. More interestingly, ARM can decide on the price point each time, without being forced to price it the same amount it previously did.

Importantly, ARM does not handle any of the production of its silicon chips, it focuses on what it does best – research – and lets its customers worry about the rest. This tactical decision has enabled ARM to be significantly less affected by the current chip shortage than its customers are. The competitive pressure on consumer electronics companies forces them to purchase the latest chip technology from ARM, regardless of whether they use that technology, to produce 100 or 1,000,000 phones.

In this case, a subscription model would be less interesting, as client companies would gain access to ARM’s new IP for no additional cost – a problem we refer to as the subscription trap.

While subscription models do generate recurring revenue, they reduce the impact of the investments companies make. In a subscription model, investments don’t provide additional value from existing customers, they maintain the perceived value customers are paying for and increase customer base. Netflix does not get additional revenue from their subscribers by making great new movies – they get new subscribers, but their current subscribers do not pay them an additional fee for those new movies.

The pattern that ARM’s business model relies on exemplifies how to steer clear of the subscription trap, and how to ensure that investments lead to additional value for the company.

Interestingly, Disney+ is leveraging parts of this pattern by making subscribers pay for its latest releases. Rather than simply uploading its latest movies to the streaming platform, it created an early access system where subscribers must pay an additional fee for access. Customers unwilling to pay this premium must wait several months until the movie is available for all subscribers. This enables Disney+ to generate transactional revenue and to reduce the cannibalisation of box office revenue that the streaming platform otherwise creates. Conversely, the decision of Netflix to not monetise new releases on its platform has meant that it also has had to essentially put a cross on releasing movies in the theaters, rarely ever using or benefiting from that channel.

While subscription models can, of course, be very successful, this pattern highlights their double-edged nature; investments serve to maintain rather to grow. In markets growing as fast as online streaming (a predicted and an astounding 18 per cent year-on-year growth over the next four years), this problem can be overcome by increased penetration. But in other markets where the number of customers is limited – the number of major consumer electronics companies, for example – companies cannot simply rely on increasing market penetration to grow. The paywall that this pattern creates resolves this problem, enabling businesses to not only create value, but to systematically capture it.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

Takeaways

The range of companies and industries mentioned above highlights the important fact that achieving recurring revenue is not a luxury limited to those businesses that can adopt a subscription model or that operate in a subscription-model-friendly industry. Not only that, but the revenue-generating patterns we outlined above might be more beneficial to your business than a subscription model would – as is the case for ARM or Microsoft.

When you iterate on your business model, don’t narrow your thinking to only include end results. Broaden your thinking to patterns – as those, unlike specific examples, can be adapted to other businesses. Each example outlined above represents a different mechanism to generate recurring revenue – and while the specifics of each business are interesting, they are not the story. The story is the pattern behind the business model, that the business uses to generate recurring revenue.

Ask yourself – could any of these patterns apply to my arena?

Alexander Osterwalder is Co-Founder of Strategyzer and one of the world’s most influential innovation experts, a leading author, entrepreneur and in-demand speaker whose work has changed the way established companies do business and how new ventures get started. Matthieu Manzoni is a Private Equity Associate at Blue Compass Management Partners in London. He previously worked as a Project Manager for Strategyzer in Switzerland before completing a Masters in Management (MIM) at INSEAD.