The spending Budget: a turnaround story (with a $40 billion problem)

While the 2022-23 budget is a remarkable turnaround, the next government must close the deficit gap without resorting to austerity, writes UNSW Business School's Richard Holden

It’s often said in business circles that good companies manage their balance sheet, and bad companies manage their P&L (profit and loss account). That same aphorism applies to governments.

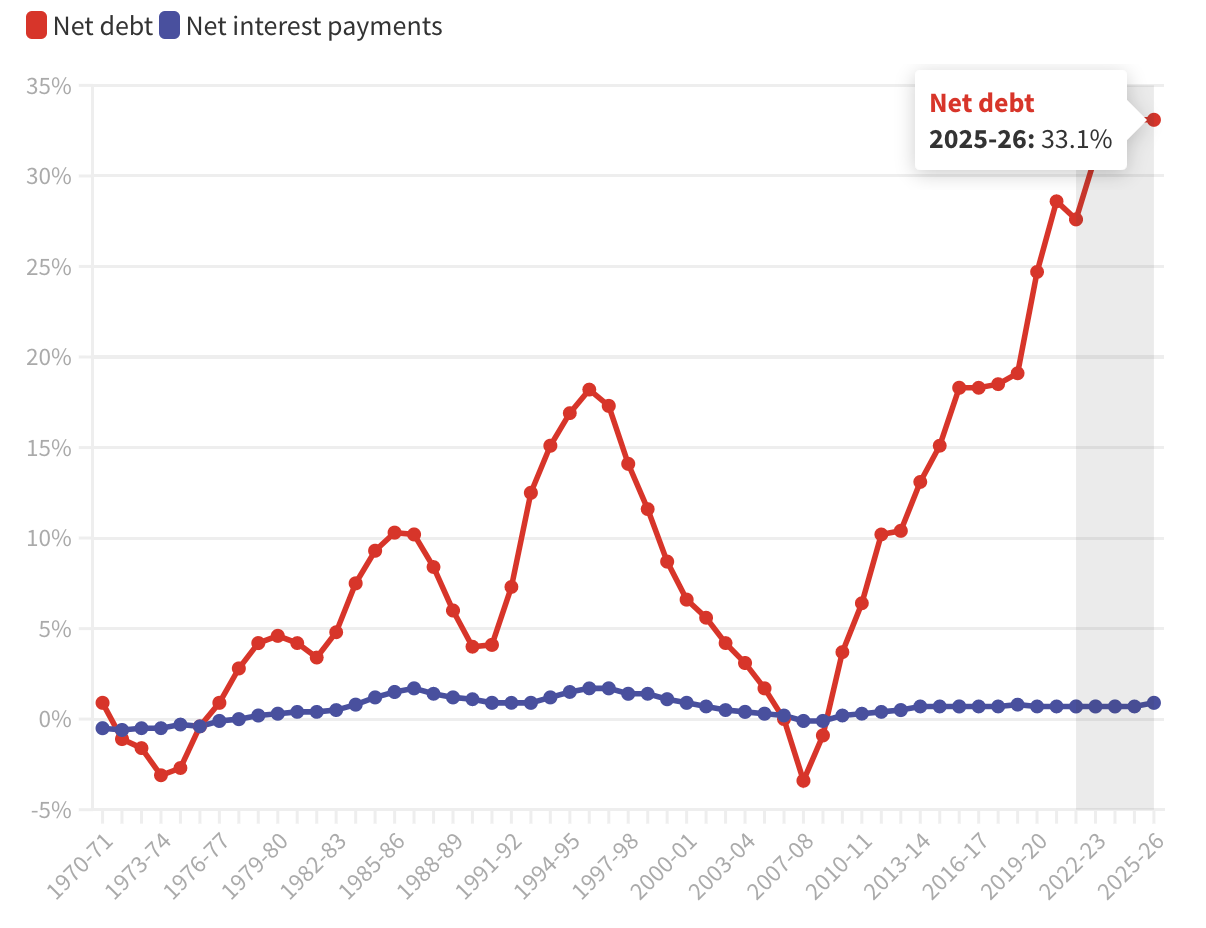

And by that standard, Josh Frydenberg’s fourth budget is a triumph. Net debt is forecast to peak at 33.1 per cent of GDP in 2024-25, compared to 40.9 per cent in last year’s budget. Net interest payments stay below 1 per cent of GDP – a better result than every year from 1984 to 2000.

Net debt vs net interest payments

This is an extraordinary turnaround, and much of it comes in the year to the end of June this year. Rather than a net debt of $729 billion by June 2022 (as forecast in last year’s budget), it is expected to be $632 billion. This reflects the stronger economy.

Unemployment is lower so welfare payments are, too. High commodity prices have helped the budget bottom line, but so too have the tax receipts from increased employment and consumer spending.

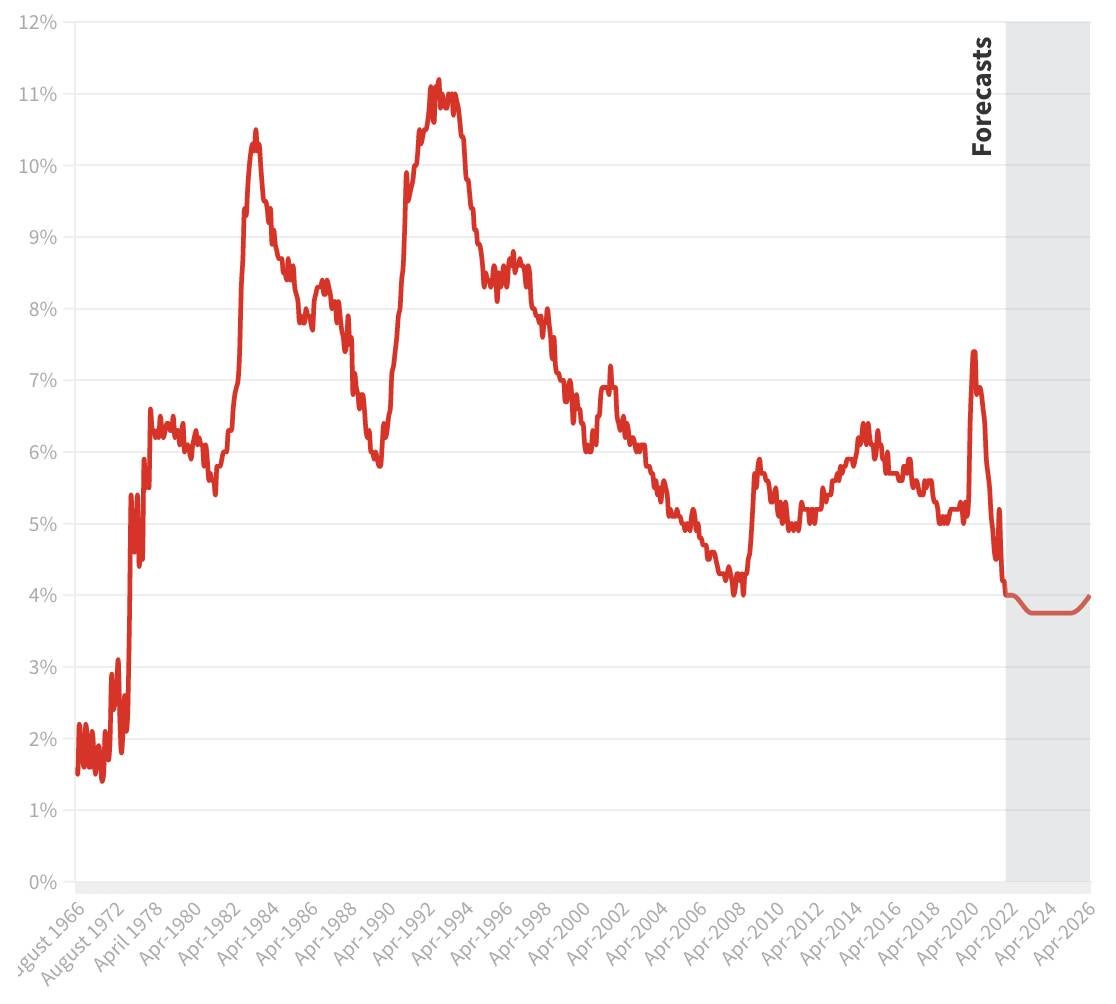

Unemployment rate

Historical vs Budget 2021-22 forecast

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, the government outlined a clear fiscal strategy: spend big to support the economy, and shrink away the debt involved through higher economic growth.

It worked. Australian GDP is 3.4 per cent higher than it was pre-pandemic. Only the United States, at 3.2 per cent, is close to that performance among the world’s seven largest economies. France is up just 0.9 per cent, Canada 0.1 per cent, while Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and Italy have all shrunk.

Amid this good news is a lingering concern. By 2025-26, the budget deficit is still estimated to be 1.6 per cent of GDP. That’s a $43.1 billion gap between government revenues and expenses.

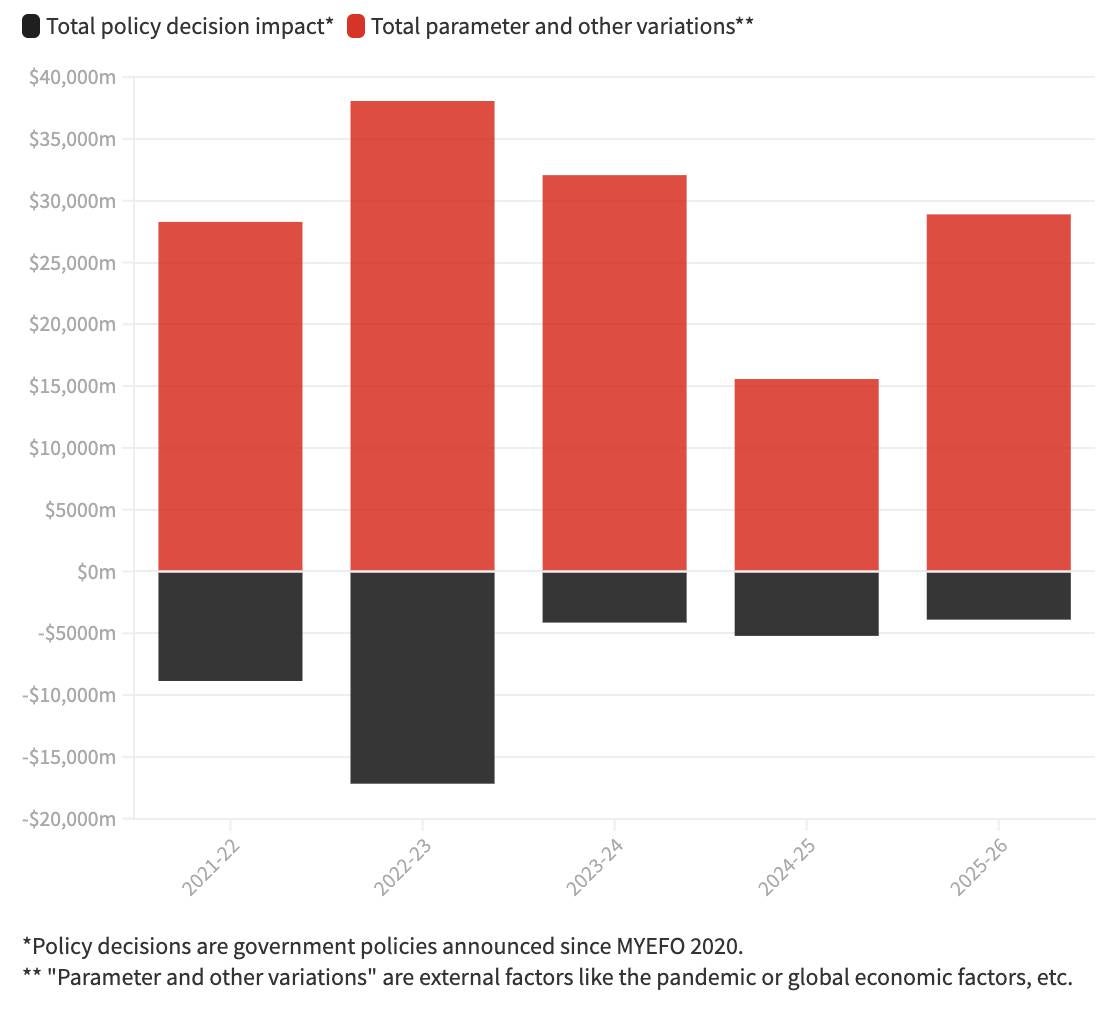

Measuring total policy decision impact

Since December MYEFO budget update, $ millions, Budget 2021-22

It is a reminder that while two governments – one Liberal and one Labor – have steered the nation through the global financial crisis and the coronavirus pandemic, they have not repaired our structural deficit.

The next government – whichever party that is – faces a difficult task. It needs to close that $40 billion structural gap without a turn to austerity that would damage the economic growth engine that’s put us in this enviable position. It’s something of a high-wire act. And it is the litmus test of good economic management.

Some big spending

It’s not hard to see why. Defence spending will grow from $35.8 billion this year to $44.5 billion by 2025-26. Given the global security outlook, it could easily go higher.

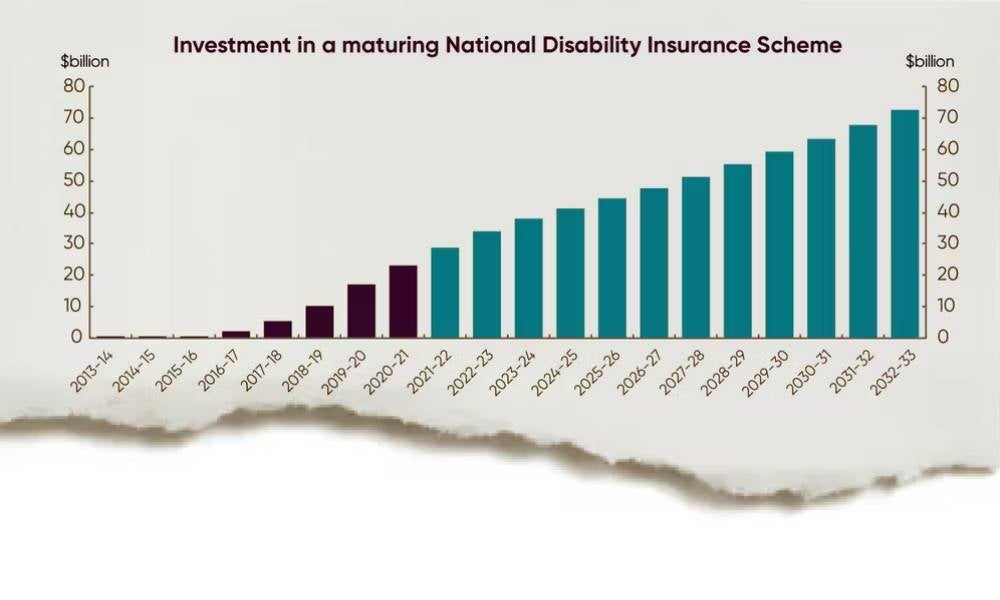

And spending on the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) will grow from $30.8 billion this year to $46.1 billion over the same time frame. That’s a growth of 10.6 per cent per annum. In fact, by 2033 the NDIS is forecast to represent more than $70 billion in government spending.

That spending is life-changing for half a million Australians. But those figures tell us such spending is only sustainable with a strong economy.

If unemployment doesn’t stay low, and economic growth is comparatively high, then spending growth in areas like the NDIS and defence will become unsustainable.

The fuel excise holiday

One hotly anticipated measure in the budget is a 50 per cent cut in the fuel excise from 44.2 cents to 22.1 per litre, for six months. Let’s be clear: this is great politics. The treasurer said in his speech: “Whether you’re dropping the kids at school, driving to and from work or visiting family and friends, it will cost less”.

This is a beautiful rendition of the time-honoured political tradition of feeling the voters’ pain. In one way this makes perfect economic sense, too. Why should households bear the risk of petrol prices bouncing around based on global conflict and decisions by the OPEC cartel?

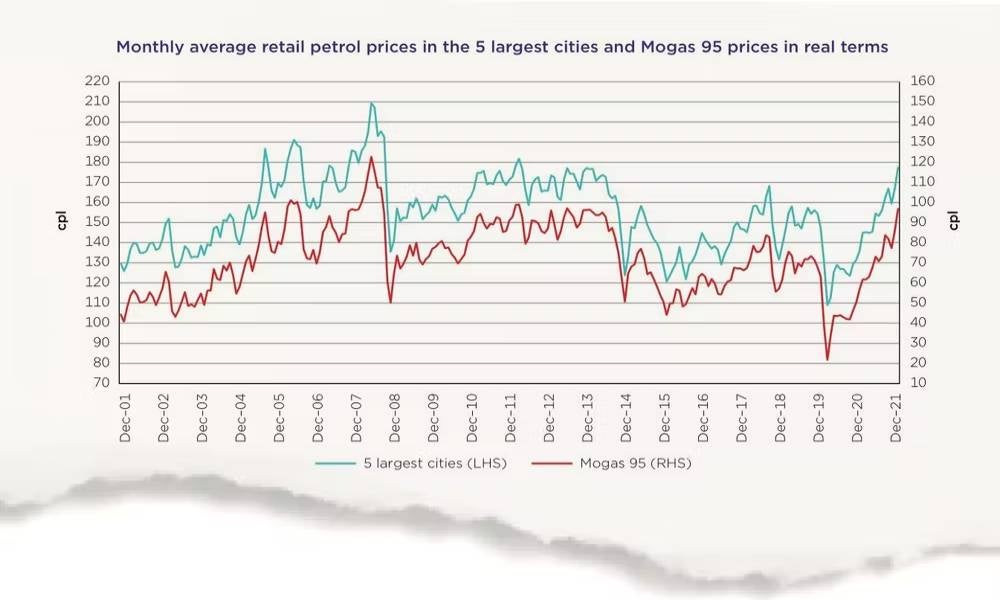

As the Australian Competition Consumer Commission has demonstrated, prices at the pump basically move one-for-one with the Singapore price of the Mogas 95 unleaded petrol sold to Australia.

By setting the fuel excise lower when oil prices are high and higher when oil prices are low, the government is acting like a big social insurance company. That’s part of their job (see Medicare, NDIS, unemployment benefits).

But there’s a wrinkle to this. According to figures from the Bureau of Statistics’ Household Expenditure Survey, the bottom fifth of households by income spend $27 a week or 3.5 per cent of their income on petrol.

By contrast, the top fifth of households spend $42 a week or 1.8 per cent of their income on petrol. So, a per litre cut in petrol benefits higher-income households more in dollar terms. It also doesn’t discourage people from driving less.

It would be more progressive (and better for the environment) to just give all households a flat rebate.

A good plan, well-executed

The tone at the budget press conference this year was in striking contrast to the announcement of the pandemic fiscal strategy in early 2020. Back then, there were sharp questions about fiscal irresponsibility, leading then-Finance Minister Matthias Cormann to exclaim: “What would you have us do?”

This time, there were a series of relatively minor questions about whether Victoria was getting enough GST revenue or if medical students who studied in regional Australia would stay there. That is the consequence of a government that jettisoned decades of political branding in March 2022, laid out a compelling plan to get Australia through the pandemic, and delivered on it.

Major cuts and new spending

- $3 billion in the next 6 months to cut the fuel excise from 44.2 to 22.1 cents per litre.

- $1.5 billion this year for a $250 one-off, tax-exempt cost-of-living payment in April for pensioners and concession cardholders.

- $4.1 billion over the next 2 years to extend and increase the low and middle-income tax offset (LMITO) for this tax year – up to $1,500 for individuals and $3,000 for couples.

- $1.1 billion for a women’s safety package over the next 4 years, including programs to help women suffering from family, domestic or sexual violence, an early intervention campaign aimed at boys and young men, and national counselling services.

- $2.4 billion over the next 5 years to add new Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme items, including drugs targeting various cancers, cystic fibrosis, COVID treatments and other chronic or terminal illnesses, and a further $525.3 million to reduce the PBS safety net threshold from July 1 2022.

- $9.9 billion ($589 million in the next four years) to double the size of the Australian Signals Directorate and increase cyber defence and attack capabilities within the next 10 years.

- $2.4 billion in total by the end of June to provide RATs to concession card holders, GPs, Aboriginal Community Health centres, and remote communities.

- $468.3 million over the next 5 years to implement recommendations from the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety.

- $2.7 billion in savings from unused fuel credits thanks to the 6 months cut to the excise.

- $2.1 billion in additional receipts over the next 4 years are expected from tax caught by ATO’s Tax Avoidance Taskforce.

- $115 million saved over the next 4 years in by reallocating 10,000 partner visas to the skilled visa stream from July 1 2022.

- $150 million in savings from the consolidated Paid Parental Leave scheme (which will fund the extension of the program to a shared 20 weeks for both partners).

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, director of the Economics of Education Knowledge Hub @UNSWBusiness, co-director of the New Economic Policy Initiative, and President-elect of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. His research expertise includes contract theory, law and economics, and political economy. A version of this post first appeared on The Conversation.