Is Labor’s superannuation tax plan as bad as feared? Or is it worse?

Labor's superannuation tax plan introduces unprecedented taxation of unrealised gains affecting future generations, writes UNSW Business School's Mark Humphery-Jenner

There has been much talk about the proposed changes to superannuation taxation. But, there are also many myths and misconceptions.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Treasurer Jim Chalmers claim that they are modest changes to ensure that people ‘pay their fair share’. However, others argue that the tax changes fundamentally alter the tax system, undermine superannuation and usher in a dangerous precedent of taxing unrealised gains.

Let’s look into what the changes are and dispel some of the myths.

The tax changes come at a time when Australia desperately needs more productivity and more economic growth.

The unfortunate picture that emerges is that the superannuation tax hike will impact all Australians – especially younger Australians. It does not only impact the wealthy, despite what politicians claim. It would undermine investment in highly productive areas. Indeed, given how the tax operates, it can literally result in wealth expropriation: you can end up paying tax on an asset that falls in value.

The superannuation changes also have indirect results, as will become apparent below. It would deter capital formation and investment in Australia by setting a bad precedent and sending a negative signal: even if it does not inspire people to leave Australia immediately it sends a message that would deter business and people from coming to Australia. In so doing, the superannuation tax hike is bad for Australians and bad for economic growth.

What exactly are the changes?

The proposed changes would increase the tax on superannuation funds with a balance above $3 million. They would take the tax rate to 30% on any increase in the superannuation balance. The government misleadingly labels balance increases as “earnings”. But these “earnings” include unrealised capital gains (aka paper profits). The $3 million threshold is not indexed to inflation or to market returns.

There is some complexity in the design. The increased tax rate applies to the “earnings” that are attributable to the portion of the superannuation fund that is above $3 million. Phrased differently, suppose a superannuation balance is $4 million, then $1 million of the fund is above the threshold. This means that 25% of any additional earnings are attributable to above $3 million balance.

Learn more: Has your super balance taken a hit? Six things you need to know

A concrete example helps to illustrate the point. Suppose a superannuation account is $5 million at the beginning of the year and increases to $5.5 million. Then, the “earnings” are $500,000. The portion of earnings related to a $3 million balance is $2.5 million/$5.5 million = 45% (approximately). So, $225,000 bears the higher tax rate. The tax liability is then 30% of $225,000, or $67,500. This can be paid for either from the fund’s assets or from a cash injection from the individual.

How many people will the tax hike impact? Is it just a tax on the ‘wealthy’?

Mr Albanese and Mr Chalmers claim that around 0.5% of people would be impacted. They argue that only a small number of Australians have balances above $3 million. However, to use blunt language: they are either lying or they do not understand their own policy.

The tax changes impact all Australians, especially younger Australians. This is because the $3 million threshold is not indexed to inflation or to investment returns. Thus, tautologically, the tax will capture more Australians over time. Indeed, given that the S&P500 generates returns of around 10% pa (with inflation around 2-3% pa), even if the threshold were indexed to inflation, it would impact more people over time.

To put this in perspective, Prime Minister Paul Keating – who founded Australia’s superannuation program – specifically stated: “This level of contributions and compound earnings will guarantee personal super accumulations in excess of $3 million at retirement.”

Even Sally McManus, leader of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) has highlighted this concern, stating that: “I do think it’s got to be indexed, because you’ve got to make sure eventually people don’t end up there.”

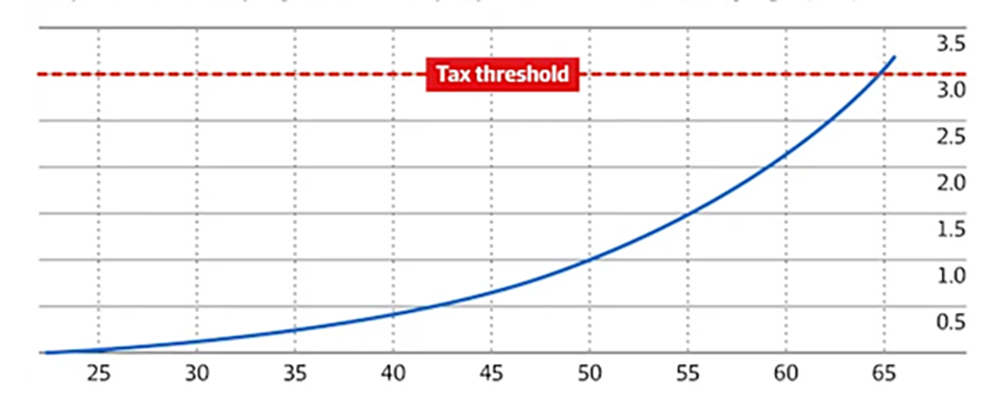

Are the concerns warranted? In short: yes, very much so. Diana Mousina, the deputy chief economist at AMP, warns that at least half of Gen Z would have a balance of at least $3 million by the time they retire. My own calculations suggest that it is extremely likely that the tax hike will capture the vast majority of “ordinary” Australians and confirm those of Ms Mousina.

Forecast superannuation balance of an 'average' Gen Z earner

It is sometimes claimed that the $3 million threshold could be adjusted in the future. However, we need only look at income tax brackets to know how fraught that is and how risky it is to rely on future adjustments. Governments have come to rely on bracket creep to increase tax revenue. After all, if the government wanted to index the threshold, it could have put that into the legislation, but it chose not to.

People must also consider the strong possibility that the threshold would be reduced not increased. People must ask themselves, once the precedent of taxing unrealised gains is set, is it truly believable that it would not then expand from $3 million superannuation funds, to even more superannuation funds?

The short of it is that politicians who claim this only impacts a small number of people are lying or simply do not understand their own policy.

Are politicians exempt?

There has been consternation that some politicians might be exempt from the superannuation tax hike. This especially relates to politicians on the old pension-style defined benefit superannuation policy. This includes people such as Mr Albanese. However, Mr Chalmers has also argued that the scheme does in fact cover everyone.

So, are politicians exempt?

The answer is slightly nuanced. The scheme does not apply to certain state politicians and administrators. This is due to a claimed barrier to federal laws impacting such retirement schemes. However, this only impacts a small number of people. It also only applies to state pension-style schemes, rather than to ‘standard’ superannuation balances.

Learn more: Why the real drain on Australians' productivity is falling wages

As to federal politicians: If the politician has a ‘standard’ defined contribution superannuation scheme, he/she is covered like anyone else. If the politician is in the old defined benefit scheme, then different rules apply. In essence, instead of paying the tax liability every year (like everyone else would do), they defer the payment until they can start drawing down their superannuation. An interest rate can apply to the deferred tax amount.

The way politicians, like Mr Albanese, are treated is beneficial. Think of it this way, suppose you can borrow at 5% pa to make 10% pa from investing, you have gained a 5% margin. The same logic applies to letting Mr Albanese defer tax payments that everyone else would have to make. Instead of spending his cash on the tax now, he can defer it and invest the money into an ASX200 or S&P500 ETF, which, on average, has higher returns than standard interest rates.

How will it impact investments in startups and infrastructure?

There are concerns that the superannuation tax hike will impact investments in startups and other unlisted assets. In turn, the fear is that it would reduce the capital available to startups, thereby undermining productivity. Is this true?

How do VC investments work? Well, if you invest directly in a startup, you should expect to lock the money up for around 10 years. Sometimes longer. Sometimes shorter. During that time, the value can fluctuate wildly. Sometimes, a company can be worth billions only to fall to zero. Indeed, even Canva has seen its valuation oscillate. These valuation changes occur “on paper”. That is, if a startup increases in value, you do not receive cash. You only receive cash when the startup is acquired or it lists on the market, which might be at a price well below what people once thought the company to be worth.

How, then, does superannuation come into play? Well, let’s start with the observation that SMSFs and superannuation funds do invest in venture capital.

Starting with SMSFs, many people use SMSFs to invest in startups. Aussie Angels – a large angel investor syndication platform – reports that around 20% of all angel investors invest via SMSFs. The rationale is obvious: investors consider the after-tax returns of an investment and consider them on a risk-adjusted basis. Startups are high-risk and long-term. Thus, what may be an attractive investment at 15% tax need not be at 23.75% tax (i.e., the marginal tax rate that most angel investors would face on long-term capital gains). Importantly, given that many startup investments are for 10 or more years, the tax rate must be low enough that your after-tax return does not even beat inflation.

What about large superannuation funds? We need look no further than the recent Guzman Y Gomez IPO, which benefited funds, such as Aware Super. However, if we dig deeper, we see that large superannuation funds appear to allocate between 5% and 10% to such private equity deals. They invest around another 10% in infrastructure-style investments and between 5% and 10% in property.

The question is then whether the superannuation tax hike would jeopardise such investments. The answer is a profound ‘yes’.

Consider what happens when a startup increases in value: under the proposed superannuation tax hike, you would need to pay a tax on that increase in value. But you have not received any cash. This creates a liquidity crunch. To begin with, this might only have a small impact. But, due to inflation, market returns, and compounding, a greater number of superannuation funds will be worth more than $3 million.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

Let’s consider a basic scenario. Suppose a person has a $5 million superannuation fund. Remember, this is very realistic for Gen Z, as discussed above. The fund is (say) 80% stocks and 20% in startups. As is often the case, the bulk of the returns from startups will come from just one company, so it is quite foreseeable that half the startup portfolio will be in one company. That is, 10% of the fund (or $500,000) is in a startup.

Now, what happens when that startup increases in value? Suppose the stock portion of the fund increases 10% (i.e., a roughly average market return). The bulk of the startup portfolio increases marginally more (say 12%), and that strong company increases significantly (say 35%). So, now the fund is worth $5.635 million. But, even if the fund does not sell a single asset, it has a tax liability of $296,000 under the new rule. Of this, around $73,550 is attributable to just that one strong startup (which has not yet been sold).

The situation is even more farcical if the startup then falls back to its original value, as is highly possible. In this case, the actual pre-tax return on that startup is $0. But the investor has paid $73,500 in tax. So, the return is negative, at nearly – 15%. This is ignoring the other on-costs, such as valuations and advice that the new superannuation rules will impose.

Let’s not mince words: this is straight-up expropriation. The investor in this scenario earned $0 on that asset over those two years, but still had to pay money to the government because of a temporary increase in price.

The net result: the superannuation tax hike dramatically increases the risk of a negative return and increases the magnitude of that negative return when investing in startups. This applies mutatis mutandis to any unlisted investment. However, the magnitude of the numbers would be smaller for infrastructure and property.

The corollary is that SMSFs and superannuation funds would reduce, or eliminate, their exposure to startups and unlisted assets. This would apply to superannuation funds as their individual members would also risk facing a superannuation tax hike liability. And, if the superannuation fund is truly acting in those members’ best interests, it should strongly consider whether it is appropriate to expose members to such risks.

It is sometimes argued that people could still invest in venture capital and startups outside of superannuation. But, this harks back to the earlier concern: An investment that might be passable at 15% tax need not be attractive at 23.75% tax. Investors consider the after-tax return on investment. Not only that, with 12% of people's earnings going to superannuation, this might be their main source of investment capital. Many people simply do not have an additional investment ‘pot of money’ of that magnitude. Or, phrased differently, people cannot simply remove money from their super to invest in their personal account because the government forces them to put money into super.

In short, the superannuation tax hike undermines investments in startups, thereby undermining productivity.

Norms and what this says about society

The superannuation tax hike raises fundamental normative questions as well. Mr Chalmers and Mr Albanese have been at pains to state that it only impacts the ‘wealthy’. However, even Bill Kelty has shot down this argument, arguing that it does not excuse ‘bad policy’.

The fundamental issue is that Labor appears to believe a policy is appropriate so long as it only impacts a small number of people. But this leads to a tyranny of the majority. Is it ‘right’ that 51% of the population can steamroll 49% of the population? What about 97% of the population steamrolling 3%? And, suppose you are in that 97% today, what’s to say you won’t be in the 3% on another policy? There simply is no limiting principle in this tax hike.

Learn more: The superannuation tax grab is neither “modest” nor sensible

Investors can see these issues: Investors would rightly conclude that a tax on unrealised gains is expropriation. Thereafter, they would fear that the government would expropriate their assets, as would happen under this tax hike (see, for example, the scenario illustrated above).

The side effect is that the people who are most impacted by this tax hike are also the most mobile – the result of which is that the tax hike could – ironically – undermine the tax base by discouraging businesses and individuals from moving here, even if people do not necessarily emigrate immediately. This, in turn, risks Australia being further left behind at a time when Australia desperately needs more economic growth.

The superannuation tax hike, therefore, undermines trust in the government more broadly. If the government is willing to expropriate assets in this area, why would you trust it in other areas?

Mark Humphery-Jenner is an Associate Professor in the School of Banking & Finance at UNSW Business School. He has been published in leading management journals, and his research interests include corporate finance, venture capital and law.