Seven ways to tell whether a private equity-backed IPO should be avoided

While investors should always examine each initial public offering on its merits, research indicates there is no reason to avoid private equity-backed IPOs, says UNSW Business School's Mark Humphery-Jenner

Private equity-backed IPOs (Initial Public Offerings) have come under significant scrutiny following several high-profile failures: but are these representative or merely anomalous blights on an otherwise well-performing sector?

For example, the proposed private-equity backed listing of Guvera music was blocked in 2016 by the ASX following concerns raised by the Australian Shareholders Association over its business model and valuation based on earnings. Guvera was looking to raise $100 million in an IPO that valued the business at more than $1.3 billion, despite the fact that it lost $81 million in the previous financial year on revenue of just $1.2 million. The move by the ASX follows Guvera re-issuing its prospectus after scrutiny from the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC).

Another notorious private equity-backed IPO was the 2012 float of Dick Smith, backed by Anchorage Capital. It ended in significant losses for initial investors and was dubbed by Forager Funds Management analyst Matt Ryan as “one of the great heists of all time”.

The high-profile the IPO of Myer, backed by TPG Capital, also performed poorly: Myer listed at $4.10 per share, fell to $3.75 per share on the first day of trade, and fell to $1.20 per share by the end of 2015.

However, several other private equity-backed IPOs have performed strongly between 2013 and 2015, including Aconex, Ooh! Media and Mantra group. This raises the question of whether the average private equity-backed IPO underperforms and what factors might investors look out for.

Do private equity-backed IPOs necessarily underperform?

So should investors make a rule to avoid private equity-backed IPOs in general? In fact, there is little evidence that private equity-backed or VC-backed IPOs underperform for investors. In Australia, from 1994 to 2005, the difference between VC/private equity-backed IPOs and other IPOs is not statistically significant.

The Australian Venture Capital Association Limited (AVCAL) in conjunction with Rothschild reports that while non-private equity-backed IPOs did perform better in 2015 than did private equity-backed ones, private equity-backed IPOs outperformed from 2013-2015. AVCAL argues that “private equity-backed IPOs strongly outperform non-private equity-backed IPOs after the first year of listing”, with private equity-backed IPOs outperforming non-private equity-backed IPOs by 23 per cent during that one year after listing.

Similarly, Deloitte argues that “the performance of private equity-backed listings suggests results are far more positive than market sentiment reflects” and that $1 invested in each private equity-backed IPO since the beginning of 2013 would yield an average return of 48 per cent by the end of 2015.

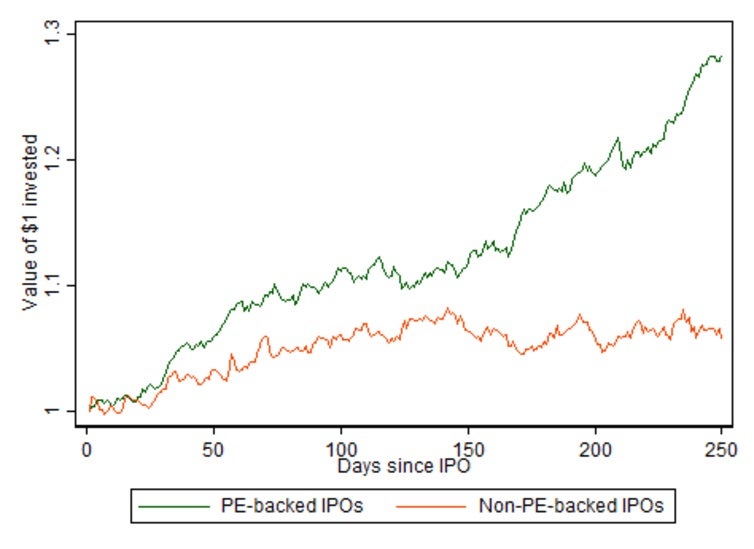

Using the set of ASX listings for at least A$100 million reported by AVCAL (and their classification of whether a firm is private equity-backed), we can look at the average value of $1 invested in each of the private equity-backed IPOs versus $1 invested in each of the non-private equity-backed IPOs.

When doing so, to avoid the possibility of outlying private equity-backed firms experiencing super-positive returns and this biasing the results, the daily return is winsorized (limiting of extreme values) and any return over 100 per cent is excluded (this adjustment actually biases in favour of the non-private equity-backed IPOs).

The below graph, which is consistent with that produced in the AVCAL report, demonstrates that private equity-backed IPOs outperform their non-private equity-backed counterparts. A similar trend appears over longer two-year and three-year time horizons (though, more recent IPOs will not yet have had the opportunity to accrue such a lengthy return history).

While there are some instances of underperformance, the average private equity-backed IPO actually performs strongly.

Seven factors investors should consider

This suggests that private equity-backed IPOs do not necessarily underperform. But clearly, not all private equity-backed IPOs will outperform either. So here are seven factors associated with post-IPO performance investors should look for:

1. Length of investment. The length of the private equity fund’s involvement with the company will help to indicate if the private equity fund actually contributed to the company. In several poorly performing private equity-backed IPOs (such as Myer and Dick Smith) the private equity fund had invested for only one to two years. When at least part of that time is also spent preparing the company for listing, this would likely be insufficient time to fully transform the company. Clearly, the time required to improve the company will depend on its complexity, but a typical situation would often call for several years of private equity-investment prior to IPO.

2. Prior litigations. Companies backed by VC and private equity funds that have been sued recently (or for whom their portfolio companies have been sued) warrant further scrutiny. Funds that have been sued have difficulty attracting future funding and if investors are reticent to invest in the fund itself, it could imply beliefs about how the fund might manage companies it lists on the market.

3. The backer’s portfolio size. VC and private equity funds that are larger and invest in more portfolio companies tend to perform worse because they spread themselves too thinly across portfolio companies, suggesting that their portfolio companies may perform worse.

4. Distance between the company and its backers. The geographic distance between the private equity (or VC) fund and the portfolio company could be a concern. For example, an overseas-based fund might face greater barriers to a successful outcome.

5. Number of backers. A company with more interested pre-IPO investors is likely to have greater growth prospects and has more scope for the disparate investors to pool their expertise to aid the company. However, there are diminishing returns to having more backers, with each additional supporter likely to have less scope to incrementally benefit the company.

6. Geographic diversification of the backers. To an extent, a backer who has supported more companies in multiple industries and multiple regions can have gained a breadth of experience and connections with which to impart the portfolio company. There are limits, with excess diversification potentially causing the fund to spread its attention too widely. The fund’s record would help to indicate whether such diversification has benefited the fund’s investments previously.

7. Private equity fund’s continued involvement in the company. It is generally a positive signal if the private equity fund continues involvement in the form of board positions or ownership stakes (exceeding the minimum time, or amount, legally required).

Essentially, while investors should always examine each IPO on its merits, there is no reason to avoid private equity-backed IPOs per se.

Mark Humphery-Jenner is an AGSM Scholar and Associate Professor in the School of Banking & Finance at UNSW Business School. A version of this post appeared on The Conversation.