Is the world ready for the invasion of the digital nomads?

Both companies and countries need to adapt their policies to accommodate and attract this new breed of worker, writes IMD Business School's Arturo Bris

This article is republished with permission from I by IMD, the knowledge platform of IMD Business School. You may access the original article here.

A new reality of technology-based jobs, autonomy and independence is upon us, giving rise to a new type of employee – the “digital nomad”– who is challenging the way we think about jobs and pay. Digital nomads – by definition, workers who relocate to another country because their job, being technology-mediated, allows them the flexibility to do so – are not a new tribe. In fact, they existed in their thousands before COVID-19. The difference to the post-pandemic dynamic is that now the decision to relocate is driven by the employee, not the employer. The pandemic period has also served as a reminder of the costs as well as benefits of remote work.

Digital nomads are also not expats. Expats work for a multinational company, report (and get paid) by a subsidiary of the firm operating in the same country. The situation of a nomad is very different: they may work in one country, get paid by a firm in another, and possibly pay taxes in a third.

Not so long ago, companies would open up shared-service centers in new countries in search of lower costs or better talent. Some functions were moved abroad to reduce costs, IT being the typical example. Today, the decision to move more often comes from the employee – causing companies to rethink offices and employment contracts.

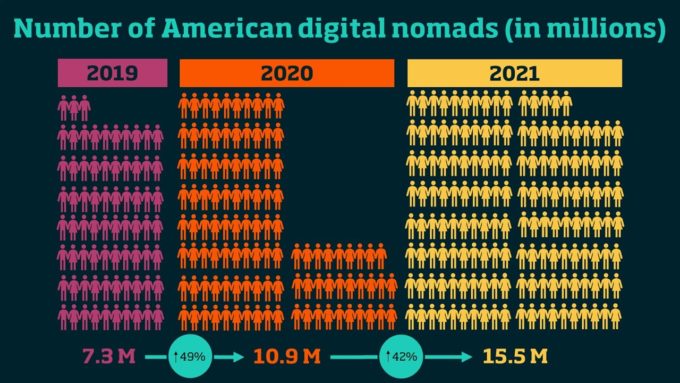

A September 2021 report by consulting firm MBO Partners finds that 15.5 million US workers currently describe themselves as digital nomads, a 42 per cent increase from 2020 and 112 per cent increase relative to the pre-pandemic years. Around 44 per cent of these are Millennials, with Baby Boomers accounting for just 12 per cent. The same report finds that 54 per cent of digital nomads plan to continue their lifestyle for the next two to three years. A 2020 survey by HSBC reveals that 80 per cent of them plan to stay in their host country for the next year at least. Only 7 per cent say they are planning to move elsewhere.

Today’s increasing number of digital nomads is changing the social, business and economic landscape in several different ways.

Changing expectations around what work provides

At the social level, the possibility of working abroad brings with it an ability to dodge the traditional office as the working space. A generation of young workers exists who, having graduated at the time of the pandemic, started their working life never having set foot in an office. It remains unclear whether, once sanitary restrictions subside, they will be willing to give up their autonomy and become confined to the office space. The advantages of being able to socialise at work (such as learning from peers, or the satisfaction that comes from belonging to a social group) are offset by those of working alone, possibly in another country.

Earlier this year, The Economist reported on a study conducted by an Asian technology company during the pandemic. The company tracked employees’ use of applications and websites when working remotely, and found that the total hours worked were 30 per cent higher than when employees were at the office. The increase in working hours did not translate into higher productivity though, as output per working hour fell by 20 per cent. However, working longer but less efficiently still resulted in higher overall output.

Digital nomads need more self-discipline but are less interested in traditional job incentives, raising new questions about the ways in which companies need to motivate employees. They are creating new habits and routines to put to bed yesterday’s rules, such as the “9-to-5” or that weekly meeting on a Tuesday afternoon. In the absence of face-to-face meetings, a new type of interaction exists whereby everybody is available at any time, but then nobody is available at the same time, given the different time zones. At IMD for instance, we teach the same session twice – once in the morning and again in the afternoon – since there is no single time when all our participants can be present.

Read more: Digital nomads: five key insights into the future of knowledge work

The social life of a digital nomad is different to that of the typical worker. Digital nomads dress down for work and dress up for dinner, as socialising happens outside of working hours. Companies such as WeWork are responding by facilitating interaction among employees of different companies; the fitness centre has become the new meeting place. This phenomenon was already underway before the pandemic.

It will become increasingly commonplace to find a graduate from a US university working in Madrid for a company based in Germany. And the impact of these workers on the countries where they live is not to be underestimated: they create a new source of globalisation – a globalisation of mindsets – by increasing the number of foreigners working in a particular city.

Some cities will also need to adjust their services, not only in order to cater for workers who operate across odd time zones, but also to satisfy a more culturally diverse demand for entertainment and leisure. There will also be an impact on urban planning and home design: if the home is the new office, residential buildings will need to accommodate this, offering homes that serve social, family and professional needs. In the 2021 IMD Smart City Ranking, we asked citizens of 119 cities in the world whether, for instance, online services provided by their city made it easier to start a business, and whether finding housing was a problem. The highest-ranking cities were also those that provided best services of this kind.

As digital nomads grow in number, they will increase the percentage of value-adding jobs in their country of residence, typically enjoying higher salaries than local employees. This will only exacerbate income inequalities. And yet, by the same token, digital nomads consume; they invest in property and generate wealth in their host country. That must surely be a win-win situation.

How to motivate the nomad

In our analysis of talent at the World Competitive Center (WCC), which culminates in our annual World Talent Ranking, we observe that top performers in terms of employee motivation are also among the top 10 most talent-competitive economies. This is not surprising. However, a consequence of the pandemic has been the so-called Great Resignation, a phenomenon that, for example, has resulted in four million Americans quitting their jobs in July 2021 (according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics).

Subsequently, one trend we have observed this year is that, despite the importance of motivation in managing talent, the world is, on average, falling down the ranks in this category. For example, while work motivation in South Africa had a score of 5.39 in 2020 (mostly using pre-pandemic data), it had fallen to 3.72 in 2021. This trend is not uniform, as we also find that the top 10 most talent-competitive countries have, on average, seen an increase in employee motivation.

On the business front, companies need to adapt to these, and other, new ways of working. The last decade saw a change in employees’ motivation, from salary and promotion to self-satisfaction, motivation, flexibility and development in the job. These are benefits that were easier to provide in the office, so there is now an unanswered question regarding the extent to which companies will be able to attract nomads eating off the same menu.

If the marked trend becomes for employees to move abroad, key corporate functions will become redundant: janitors, security personnel, catering and restaurant staff among them. This will lead to productivity increases, but potentially to more unemployment, too, in companies and countries that are not able to adapt by providing new forms of work. Ultimately, companies will need to remove barriers so they can give certain employees carte blanche over which country they want to live in. It’s quite a radical change in scenario to pre-pandemic operations.

The macroeconomic effects of the digital nomad

The competitiveness of companies and countries depends on where employees live. For companies, it’s a case of cost optimisation. In the case of countries, talent attraction and retention can change drastically as employees’ whereabouts ebbs and flows. National regulation, then, needs to accommodate this.

Countries such as Switzerland do not have the legal tools to allow a temporary worker to stay once their contract has expired, depriving them of the chance to find a new job in the time frame needed. Singapore, on the other hand, has become a successful economy by making it easier for foreign workers to establish in the country, especially when compared to its neighbours.

If countries want to remain competitive, they need to make it possible for local companies to recruit foreign talent – that is, talent living abroad, not necessarily talent of a different nationality. This requires very specific regulation, fiscal rules, and – in some countries – the complete removal of quotas for nationals. Cases in point are the “Emiratisation” and “Saudisation” initiatives of the governments of the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, which are aimed at using its citizens in a meaningful and effective way in the public and private sectors.

On the other hand, countries will gain the upper hand if they are able to attract employees working for companies abroad, as they will reap the benefits of them paying taxes and supporting the economy. But this won’t happen unless governments can generate the necessary conditions for individuals to be attracted to the country in the first place.

Read more: Lessons from the Great Resignation in how to find meaning at work

In the past two years, three countries have stood out with good policies of this sort. Portugal introduced fiscal advantages for Non-Habitual Residents (NHR), meaning they can avoid income taxes for 10 years. The country even has a specialised website (digitalnomads.pt) to provide guidance about housing and formalities. Estonia has done something similar with workers in the IT sector. Earlier this year, Thailand announced a plan to attract one million digital nomads to the country.

The demise of the salary as the main way to lure talent

One of the most important determinants of the competitiveness of a country is the quality of its education system. However, when companies hire abroad, and when workers in a country work for a foreign company, the role of the national education system is undermined. Why would a government invest in education if the national talent pool leaves the country or domestic companies can recruit talent from anywhere?

If fact, as digital nomads earn salaries determined by their company’s country of origin, factors beyond salaries will drive talent attraction and retention: quality of life, availability of housing, safety, weather, and opportunities for personal development and entertainment.

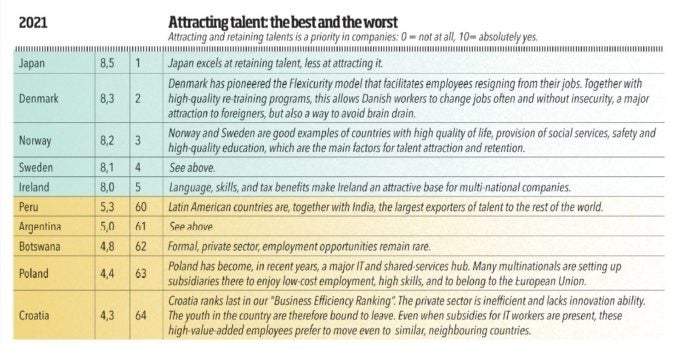

The chart shows the ranking of talent attractiveness of 64 countries from the 2021 IMD World Talent Ranking. Our measure is a survey question asking executives in different countries whether “attracting and retaining talent” is a priority in companies. The top countries are Denmark, Luxembourg and Estonia. Croatia, the Slovak Republic and Poland rank at the bottom. For these less attractive countries, measures to attract digital nomads are of paramount importance.

A new type of ‘residential’ status?

Digital nomads are not permanent residents. And they don’t aspire to become permanent residents. Countries need new legal figures to adapt to such a status. Current immigration laws foresee that the ultimate objective of an immigrant is to become a national of the host country. This is not true anymore and therefore citizenship rights must be granted much earlier in most countries, in order to integrate nomads quickly.

Digital nomads are a reality. Are governments willing to favour the attractiveness of their countries by making special rules for this new type of worker? Not all societies will be willing to accept the social implications of such positive discrimination. It is also foreseeable that in a context in which digital nomads boost real-estate prices and increase income inequalities, there could be a backlash against them.

Arturo Bris is Professor of Finance at IMD. Since January 2014 he is also leading the world-renowned IMD World Competitiveness Center and he is Program Director of the Navigating Fintech Innovation and Disruption program.