Calling all real-world economists: your hour is now

With greater access to data combined with advances in methods, modelling and computing power, the next generation of well-trained economists can have more influence than ever, writes UNSW Business School’s Professor Gigi Foster

The crisis of the past six months has left economies around the world reeling, companies in freefall, and politicians scrambling for words to match the moment. Individuals and companies in Australia and overseas are still living in suspended animation as they wait for the unprecedented uncertainty of 2020 to give way to clear future trajectories.

What will our society look like in a year’s time? Which people, industries, and countries will end up on the other side of COVID-19 as the winners, and which as the losers? What can governments in Australia and elsewhere do to help – and what should they avoid doing? How can we learn from what has happened and prevent the mistakes of this period from being repeated?

In a crisis moment such as the COVID-19 phenomenon has presented to the world, applied economists are uniquely well-trained to keep their heads. The back-room advisors of government and industry, not always on the front page but often deeply respected, applied economists make pragmatic assessments about how to use the powerful tools of economic analysis to get the most bang for society out of each buck available.

Let’s take a look at some of these unsung heroes and why they’ve mattered, now and in the past.

Heroes of their times

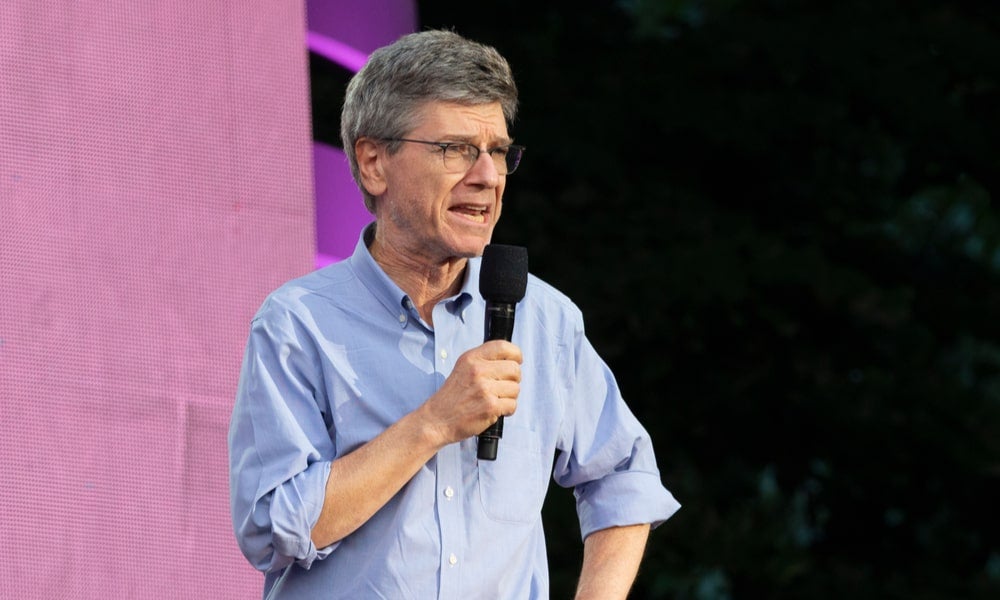

Jeffrey Sachs: His work in economic development and environmental advocacy put Sachs twice on the iconic Time Magazine list of the world's 100 most influential leaders. He was head of the Earth Institute from 2002 to 2016 and has been Professor at Columbia University since 2016. He is also the Special Advisor to UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres (initially to Guterres’ predecessor Ban Ki-moon) on sustainable development issues.

Christina Romer: Professor of Economics at the University of California Berkeley, Romer was appointed by Barack Obama to the powerful position of Chair of the Council of Economic Advisors, a position in which she served from January 2009 to September 2010. She was the co-architect with Larry Summers and Peter Orszag of the $800 billion stimulus plan that Congress passed to drive America’s recovery from the Great Recession.

Ian Harper: Closer to home, Ian Harper, Dean of the Melbourne Business School, made a formidable contribution to Australian economic life with his work as Chair of the Commonwealth Government’s Competition Review from March 2014 to March 2015. Earlier in his career, from December 2005 to July 2009, he was the first Chairman of the Australian Fair Pay Commission, helping set labour market policy for the land.

Christine Lagarde: Paris-born Lagarde is an unusual illustration of how a highly influential practising economist can make astounding contributions with little theoretical training. Her resume glitters with service as France’s trade minister from 2005-7 and its finance minister from 2007-10. In 2011, she succeeded Dominique Strauss-Kahn as Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund and left that role when she was appointed President of the European Central Bank in October 2019, a position she still holds. In the same year, Lagarde moved up Forbes Magazine’s annual list to be named the Second Most Powerful Woman in the World.

Darrick Hamilton and William (Sandy) Darity: Hamilton and Darity are applied economists who collaborated on a federal program designed to erase racial inequality in the US called ‘baby bonds’. The idea is for the government to issue bonds in the name of poor minority infants, redeemable when the children reached adulthood to use for school, a start-up business, or some other developmental purpose. The program is currently enshrined in legislation introduced by US Senator Cory Booker and Representative Ayanna Pressley. Hamilton is Executive Director of the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University. Darity is a Professor of Public Policy at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy.

Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Romer, speaking recently to the Vienna Behavioural Economics Network, offers this view: “My contribution has been mainly as a theorist, and in economics, we tend to give a little too much weight to the … pronouncements of the theorists. What theory can do is suggest possibilities, but it’s only evidence – collected through experiments, collected, however – that can actually tell us what’s true.” As he notes, “data beats theory every time” – remarking on how the recent shift away from pure theory and towards real data is particularly opportune at this historical moment.

Theory is blind without application

In 1936, as America emerged from the world’s last great economic downturn, John Maynard Keynes opined that “practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.” By these dark “intellectual influences”, Keynes was referring to competing theories about how best to run the world, including whether capitalism or communism should work better to organise our lives – arguably the biggest economic question of the past 200 years – that variously drove the resource-allocating instincts of the policy-making cadre.

Big theories like these have since had decades to compete against each other on the global stage of real-world application for the crown of “useful to society”. Societies have tried out smaller-scale theories too, like trickle-down economics, austerity, quantitative easing, Keynesian stimulus, monetarism, and many others, and seen the results. The data have in many cases delivered a winner. This practical testing and selecting ideas that work for people, business, and the government is the bread and butter of applied economists. In the coming economic recovery, it’s knowing which ideas actually work that will make all the difference.

In the past, limitations in data and methods constrained our ability to put economic theories to the test. With the recent proliferation in data and advances in methods and computing power, these limitations are greatly reduced. The next generation of well-trained economists who are prepared to think pragmatically and grapple with real data have more usefulness, more sense, and hence more influence than ever, in our corner. We’re in huge demand. Why not join us?

Professor Gigi Foster is Director of Education for the School of Economics at UNSW Business School. UNSW Business School has recently launched a flexible two-year Master of Applied Economics, which has been developed to provide professional economists with practical skills underpinned by a broad and advanced knowledge base to prepare for the future of economics. For more information please contact Dr Minxian Yang, Senior Lecturer and Postgraduate Coursework Coordinator in the School of Economics at UNSW Business School.