Why the RBA wants to cut unemployment, not soaring house prices

The RBA has said it will look to zero in on unemployment, but this puts the onus on the government to take action to rein in home prices, writes UNSW Business School's Richard Holden

Ahead of the definitive official read of the economy from the treasury in the budget on Tuesday, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has given us two special insights into its own thinking in the space of 14 hours.

They suggest that (first) the economy is improving, and (second) the bank is not going to let up on driving that improvement, not for anything — including concern about climbing home prices — until it has pushed unemployment down and wage growth back up to where it believes it should be.

The first insight was in Deputy Governor Guy Debelle’s Shann Memorial Lecture delivered on Thursday night (6 May). The second was in the following day's Statement on Monetary Policy.

Growth without inflation

The statement emphasised that the, although the bank expects economic growth to bounce back fairly strongly, getting inflation back within the bank’s 2-3 per cent target band and getting wages growth up, will take much longer. As the statement put it: "despite the stronger outlook for output and the labour market, inflation and wages growth are expected to remain low, picking up only gradually."

On one measure just 1.1 per cent, the lowest on record, underlying inflation is to climb to 1.5 per cent over the course of 2021 before gradually climbing to close to 2 per cent by mid-2023. It’s well short of the bank’s target of 2-3 per cent which is only likely to be achieved with much higher wages growth driven by much deeper inroads into unemployment.

Those inroads will be easier to achieve if COVID is firmly under control.

The bank explicitly linked its forecasts of an improving economy to an assumption that Australia’s vaccine rollout accelerates in the second half of the year. It could have added to that (but didn’t) the importance of getting purpose-built quarantine facilities up and running.

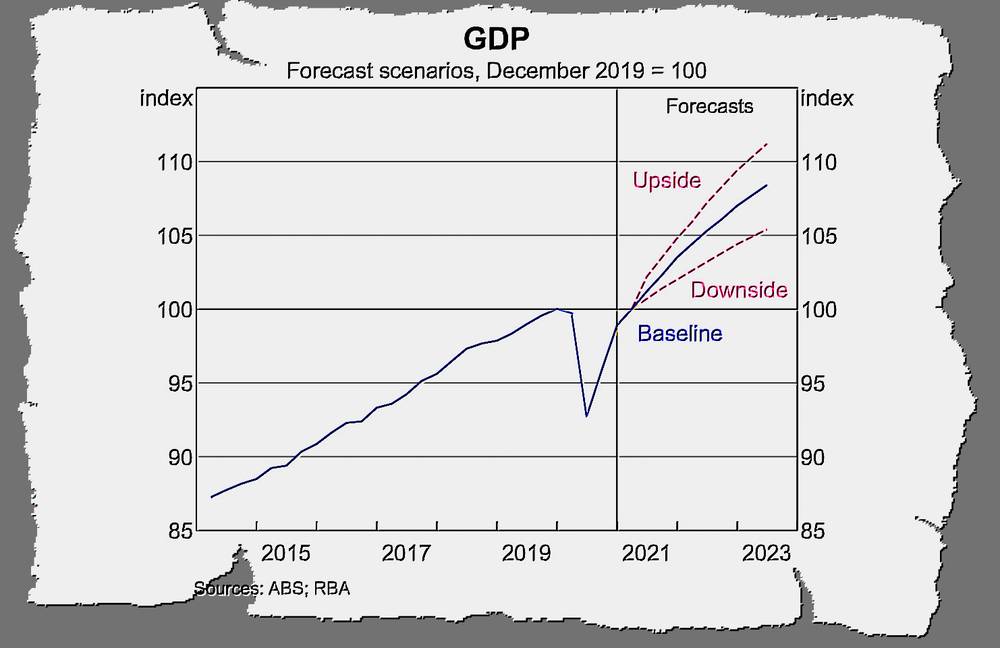

Its baseline forecast has economic growth of 4 per cent in the year to June 2022 and 3 per cent in the year to June 2023.

But there is a fairly wide range around its downside and upside scenarios.

Economic growth might be as low as 2.5 per cent or as high as 5 per cent in 2022 and as low as 2 per cent and as high as 3 per cent in 2023.

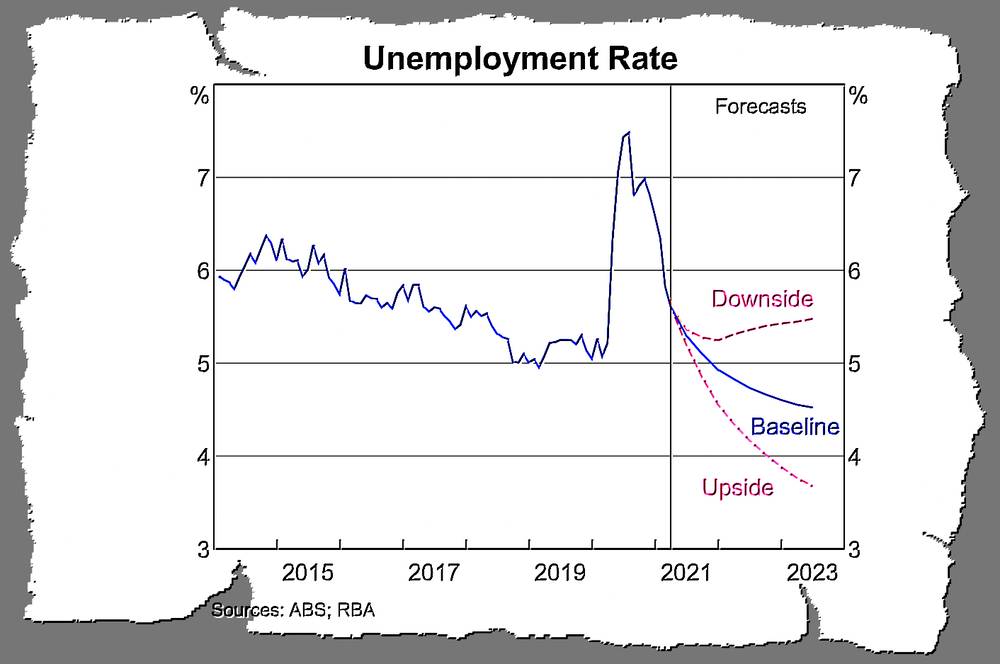

Similarly, the unemployment forecast is somewhere between 4.25 per cent and 5.25 per cent by June 2022 and in a very wide range of 3.75 per cent and 5.5 per cent by June 2023.

These forecasts produce below-target inflation forecasts of between 1.5 per cent and 2 per cent in June 2022 and 1.5 per cent to 2.25 per cent in June 2023.

What the bank will do to help drive the upside scenario, and what else will need to happen, was laid out by Debelle in Thursday night’s Shann Memorial Lecture.

The Debelle Doctrine

Adjectives like “seminal” are bandied about liberally these days, but for me, Debelle’s speech on Monetary Policy During COVID was a masterpiece.

Read more: Should the government worry about its record debt in the federal budget?

He began by outlining the suite of measures the bank introduced from the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020. They involved:

- cutting the cash rate to a record low of 0.25 per cent and then cutting it again to 0.1 per cent

- undertaking to not increase the cash rate target until the bank is confident that inflation will be sustainably within the 2–3 per cent target band

- cutting the rate paid on private banks’ exchange settlement balances with the bank to 0.1 per cent and then to 0.0 per cent

- buying enough three-year government bonds to target a yield of 0.25 per cent, later 0.1 per cent

- guaranteeing to buy $5 billion of five-year and ten-year state and Commonwealth week-in week-out whatever the economic circumstances

- buying bonds as needed to address the “dysfunction” in the bond market

- offering banks cheap lending finance through a new term funding facility

- ensuring that the financial system has sufficient liquidity

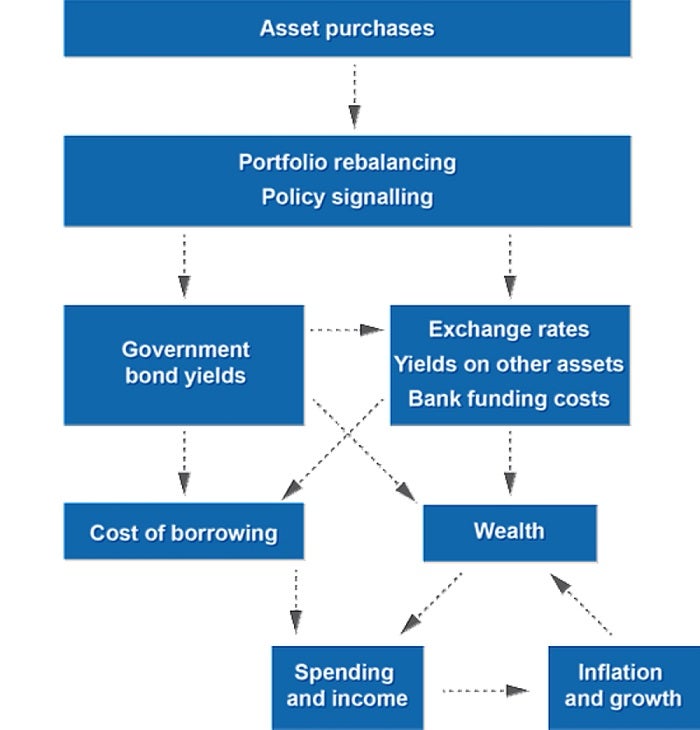

Debelle methodically described how each of these measures is likely to flow through into economic activity. That is, he articulated what economists call the “transmission mechanism” — how the measures work. As an example, the following chart he provided summarises the transmission mechanism for bond purchases.

And then he delivered the setup for the punchline. The tools the bank is using might affect all sorts of things, including house prices. But the bank plans to focus on just one thing – getting unemployment down until it gets inflation back up to its target band.

Then the punchline itself: the bank will do this even if it leads to higher house prices: "there are a number of tools that can be used to address the issue. But I do not think that monetary policy is one of the tools. Monetary policy is focused on supporting the economic recovery and achieving its goals in terms of employment and inflation."

It was important to remember that while housing prices may not rise as fast without low interest rates, unemployment would definitely be materially higher without low interest rates. Unemployment has serious consequences.

Read more: Three economic facts point to a big-spending federal budget

What it all means

The Debelle Doctrine is that the bank will focus on a narrow range of objectives, and will not be timid about using the tools in its arsenal to achieve them. This may not be a seismic shift, but it is significant.

It gives the bank a much clearer focus; it gives others a much better way to judge how it is performing; and it makes clear that if the government is concerned about rising house prices, it’ll have to do something itself (perhaps by tightening the tax rules governing capital gains and negative gearing).

Debelle produced a clear, precise, and authoritative statement of what the RBA can, should, and will do. In a word, it was gubernatorial.

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, director of the Economics of Education Knowledge Hub @UNSWBusiness, co-director of the New Economic Policy Initiative, and President-elect of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. His research expertise includes contract theory, law and economics, and political economy. A version of this post first appeared on The Conversation.