Guy Kawasaki: What Silicon Valley won't tell you about innovation

Guy Kawasaki distils lessons from Apple, Canva and Silicon Valley startups into a framework for creating products and services that are both unique and valuable

When Guy Kawasaki knelt beside Steve Jobs for a historic photograph in front of the Macintosh division building in 1984, he could not have predicted how the lessons from that era would shape his understanding of creativity three decades later. "This is the only instance where Steve Jobs ever got on his knees for anybody," recalled Mr Kawasaki, a successful Silicon Valley venture capitalist and co-founder of Garage Technology Ventures, a seed and early-stage venture capital fund that invests in start-ups and entrepreneurs looking to transform big ideas into game-changing companies.

The former Chief Evangelist for Apple and now Chief Evangelist for Sydney-based high-profile startup Canva has years of experience in understanding what separates organisations that create breakthrough innovations from those that merely iterate on existing ideas. He recently delivered a presentation on innovation and value creation at the World Business Forum Sydney and drew on insights from 300 interviews conducted for his podcast, Remarkable People.

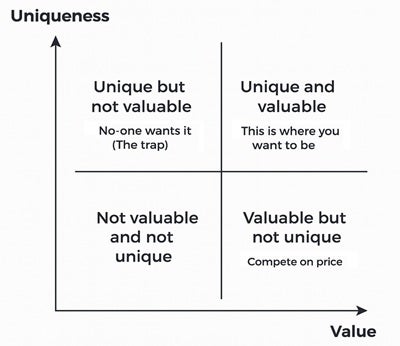

The value-uniqueness matrix

Mr Kawasaki, who also serves as an Adjunct Professor at UNSW Sydney, started by introducing a two-by-two matrix that forms the foundation of his value creation framework. The vertical axis measures value, while the horizontal axis measures uniqueness. He explained that products or services that are valuable but common force companies to compete on price. Those that are common but not valuable occupy what he termed "the dumb square." The category he labelled "the sad corner" contains offerings that were unique but lacked value.

"The upper right-hand corner, that's where you do something unique, and you do something valuable. I think that the goal of all creativity and innovation is in that upper right-hand corner, where you do something unique and you do something valuable," said Mr Kawasaki.

He cited the iPod as the product that personified this quadrant when it launched. The device held 10,000 songs, featuring a user interface that allowed people to navigate, offered music at 99 cents per song, and enabled legal downloads. No other product combined these features, which is why he said the iPod was a success.

Finding pain points and becoming the customer

A key principle in understanding value creation involves identifying customer pain points. Mr Kawasaki distinguished between what Silicon Valley calls “painkillers” and “vitamins”. "In Silicon Valley, we have this dichotomy where there's painkillers, and there's vitamins,” he said.

“Vitamins are supplements that theoretically make you healthier and better. There's not a lot of scientific evidence that backs that up. Mostly, it's a lot of people who are trying to just hustle you to buy vitamins and supplements. On the other hand, there are painkillers. I am a person who gets migraine headaches, and I'll tell you something, when you have a migraine headache, you will pay almost anything to get rid of that headache."

Learn more: How investors and entrepreneurs can successfully play the forecasting game

The second principle pushed beyond market research. Mr Kawasaki argued that reading reports provides insufficient insight for innovation. Rather, companies need to go and see customers in pain, or better yet, be the customer. "It's much better if you want to be creative to actually, at the very least, go and see your customer in pain, watch them in pain. Now, even better than going and seeing is going and being," he said.

He shared a story about marketing consultant Martin Lindstrom, who worked with a pharmaceutical company that wanted to get closer to customers. Rather than commissioning focus groups, Mr Lindstrom took the executives into a room and made them breathe through straws. The exercise simulated the experience of living with asthma, the condition their products treated. "You wanted to be closer to the customer," Mr Kawasaki recounted. "I made you as close as possible. I made you into a customer. You're a pharmaceutical company. You treat asthma. This is kind of what asthma is like, where you draw [on that straw] your whole life. So, now you're more than closer to the customer. I mean, you're actually the customer," Mr Kawasaki recounted.

Working backwards and asking simple questions

Mr Kawasaki argued that companies often work forward from their capabilities rather than backward from customer needs. He used Kodak as his cautionary example. "You need to wrap your mind around Kodak – the Kodak that none of us ever use anymore,” he said. “Kodak invented the digital camera. I mean, every time I think of this story, I think, how could this be? If you invented the digital camera and you stuck with it, you would be Sony or Nikon, or maybe you would be Apple."

Rather than choosing to evolve its business, Kodak remained committed to producing photos through chemicals on film and paper. Mr Kawasaki explained how the company defined itself by its production process rather than its customer purpose. "The problem is that they were working forward from what they like to do, what they have been doing, what they were good at doing," he said. "They were working backwards from the customer. If you think about it, when you take a picture, what you are doing is not chemicals. I don't think you wake up in the morning saying, ‘I'm going on a vacation to Sydney. I need to buy some chemicals.’”

Rather, customers purchase the ability to capture and preserve experiences. When people travel, for example, he said, they want to know immediately that they have captured their moments. The analogue process of taking photos forced them to wait days or weeks for processing. "What people want is the preservation of memories,” said Mr Kawsaki. “That's the business that Kodak should have figured out, that we are in the preservation of memories business.”

What kind of questions lead to innovation?

Mr Kawasaki also discussed the types of questions that can help nurture innovation. Companies often ask about market domination and achieving trillion-dollar valuations, but he proposed simpler alternatives. "It's been my observation that people who are the most creative ask much simpler questions, much humbler questions, that are maybe easier to ask, but maybe much harder to answer," said Mr Kawasaki. These questions include, for example: Is there a better way? Isn't this strange? Why has no one done this before?

The 3M story of Post-it Notes is an example of the second question. One of 3M’s business lines involves adhesives, and Mr Kawasaki explained that it made an adhesive that was very weak and could lift off surfaces without leaving a trace. “Isn't that strange? We tried to create a really strong glue, and we created a really weak glue," he said. However, 3M recognised that the weak adhesive had applications for temporary markers that could be removed and repositioned, and this simple observation transformed a failed experiment into a successful product.

Jumping curves and shipping imperfect products

Another principle challenges companies to move beyond incremental improvements. Mr Kawasaki argued that innovation rarely occurs on the “current curve” of product development. For example, he traced the evolution from harvesting ice to ice factories to refrigerators. "Either get to the next curve, or you've got to create the next curve," he said.

In the process, Mr Kawasaki spoke about the principle of "don't worry, be crappy." He showed an image of Steve Jobs introducing the Macintosh 128K in 1984. "The Macintosh 128k did not have enough RAM. There was hardly any software. You could make the case that Mac 128k was a piece of crap – but it was a revolutionary piece of crap," he said. The machine represented innovation on a new curve rather than an iteration of existing computers.

Subscribe to BusinessThink for the latest research, analysis and insights from UNSW Business School

"When you truly do jump to the next curve, I think the market will forgive you for a few years to have elements of crappiness. Now, don't get me wrong. I am not saying you should ship crap,” he said. “I am saying that if you jump the curve, you can have elements of crappiness – but you should be jumping to a new product innovation or creativity."

Developing and backing winning products

Mr Kawasaki also spoke about the importance of internal product use. He described this as "eating what you cook" and illustrated the concept with an example from IKEA, whose employees often furnish their offices with IKEA products. In the process, they learn what works about their own products, what doesn’t work, and come up with ideas for improvements through everyday use. Mr Kawasaki observed that companies that fail to use their own offerings often ship flawed products.

Acknowledging uncertainty in predicting success is also crucial in the innovation process. Mr Kawasaki compared two theories: placing all resources in one basket versus distributing resources across multiple options. His experience in writing 18 books and with numerous product launches taught him that the process of prediction is unreliable.

"There’s a theory that you put all your eggs in a basket, and you guard the basket very well. I don't buy that theory anymore,” he said. “My theory is, you get a lot of eggs. You have eggs all over the place, because you never know which one is going to be the chicken. You have to do a lot of stuff. You have to take a lot of risks. You have to take a lot of chances."

He described how Silicon Valley actually worked, contrasting the public narrative with the reality. "What we do in Silicon Valley is we throw a lot of s*&t up against the wall, and one out of 400 of those s*#ts sticks to the wall. We go up to the one that's stuck to the wall, and we paint the bullseye around that one, and we say: ‘We hit the bullseye. We are so smart. We are experienced entrepreneurs. We are experienced investors. We know exactly what we do. We knew that was the one,” he said. “Well, I hate to tell you, pal, but you know, that's bulls&*t."

He explained how Melanie Perkins made about 300 pitches before securing funding for Canva. "So, if everybody knew that Canva was going to be so successful, what happened to the 299 supposedly smart investors who blew her off?" asked Mr Kawsaki, who reiterated the importance of planting numerous seeds and nurturing the ones that show promise.

Making good decisions in an AI world

Mr Kawasaki also spoke about artificial intelligence. While acknowledging concerns about hallucinations and hype, he argued that AI will soon become as normal as the internet. He recalled scepticism about online commerce from 15 years earlier. "Imagine today that you were saying, ‘You know, 15 years ago, I said, ‘What is this internet thing? Why would I need a website? I got all the business I can handle. I got an 800 number. I got a fax machine. That's all the marketing I need,’" Mr Kawasaki said. He predicted that AI would follow the same trajectory.

Mr Kawasaki explained how he used AI in his writing. " I use AI literally every day,” he said. “And at least once a week, I say to myself, ‘How did I ever do this before?’” said Mr Kawasaki, who compared using AI to conducting a symphony. "You should be thinking you're a band leader, you're a symphony conductor. So sometimes you need Canva, sometimes you need ChatGPT, sometimes you need Claude, sometimes you need Grammarly."

Making the right decision and making the decision right

Another principle that Mr Kawasaki shared came from Ellen Langer, a psychology professor at Harvard whom Mr Kawasaki interviewed for his podcast. She distinguished between making the right decision and making your decision right. With big data and AI, companies often focus on analysis and prediction, but Prof. Langer argues that arriving at the right decision is impossible in many situations due to changing conditions and unpredictability.

Learn more: The bullseye framework: a perfect business model canvas teammate

"Instead of everybody trying to just do what is normal today, which is make the right decision, what you should really do is make your decision right, so you take your best shot,” he said. “Use AI, use big data, use all kinds of focus groups, whatever the hell you want to – but at some point, you make a decision, and from that point forward, it's no longer about making the right decision. It's no longer about second-guessing if you have made the right decision. What you should be thinking is, ‘how do I make the decision that I made right at this point?" Mr Kawasaki said.

He illustrated this principle with a surfing metaphor, showing a video of his daughter competing in a longboard competition. He explained that surfing primarily involved decision-making. "I think that about 95% of surfing is trying to make the right decision. You have to decide where to sit in the water. You have to decide on which way, you have to decide on what direction, you have to decide on when you should pop up. You have to decide when you should kick out,” he said. “You have to look at the competition, you have to figure out how much time is left in the heat – there's an endless number of variables to figure out in surfing.

“This is a metaphor for life. We would all have the perfect company with perfectly qualified employees in a large and growing market, and your technology is defensible; nobody can do what you can do. But that's not the real world," explained Mr Kawsaki, who observed that companies rarely enjoy conditions where everything aligns. Rather, once they commit to a direction, he said the focus needs to shift away from whether they had chosen correctly, to how they would make their choice succeed.