Budget update: no sign of a return to austerity as Frydenberg prevails

The economy looks to bounce back in the short-term but the predictions for long-term growth are not as optimistic, writes UNSW Business School's Richard Holden

Thursday’s Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook reminds us of some uncomfortable truths.

In the short term, MYEFO forecasts the economy bouncing back, with deficits shrinking, unemployment falling, and growth rebounding. But that will largely play out in the next financial year, 2022-23.

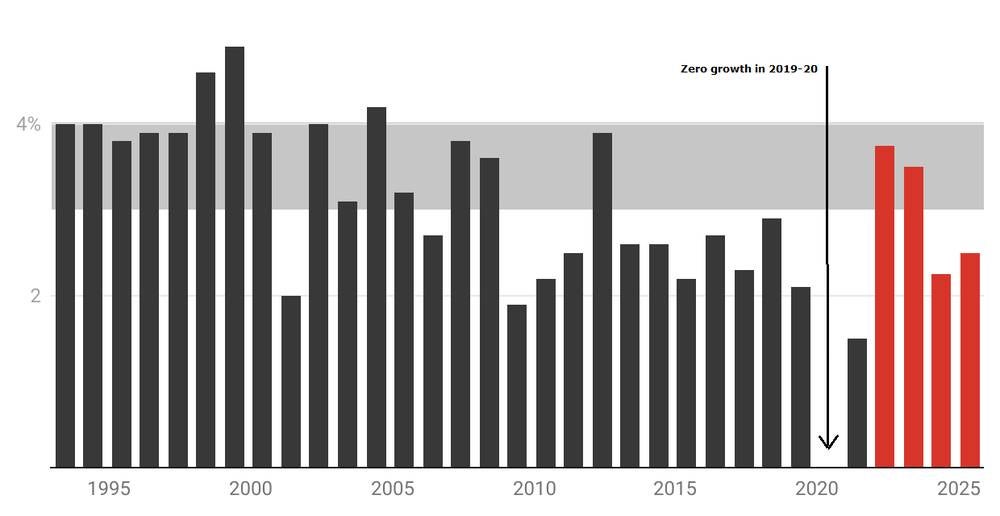

Beyond that, the forecasts have us returning to the relatively low-growth economy we endured before COVID. Economic growth is forecast to be 3.25 per cent in this financial year, back briefly in the 3-4 per cent range we used to regard as normal.

Next financial year it is forecast to remain high at 3.25 per cent before falling back to 2.25 per cent and then 2.5 per cent, well within the historically low territory it occupied before COVID.

Annual financial year GDP growth, actual and forecast

Unemployment, which is forecast to fall to an impressively low 4.25 per cent by mid-2023, is forecast to stay there in the following forecast years, improving no further.

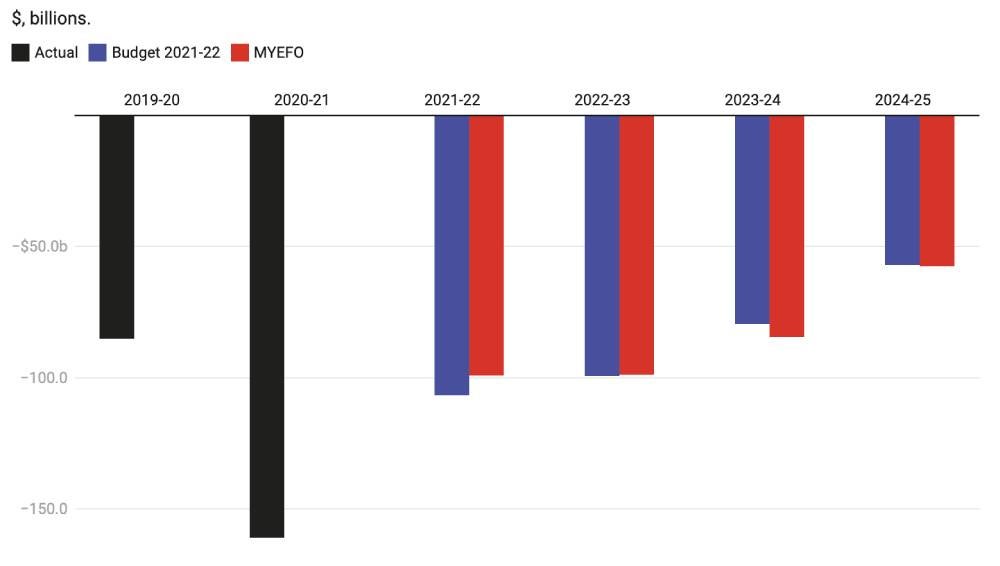

The broader takeaway is that not only did the government do the right thing by providing massive financial support during the pandemic – some A$337 billion of it – it is continuing to do the right thing by not prematurely withdrawing it.

The ongoing (if significantly smaller) budget deficits in coming years are a testament to the lesson learnt about the importance of spending to get economic growth up, and unemployment down.

Underlying cash balance

Perhaps the most uncertain forecast is for wages. Growth in the wage price index is forecast to increase from 2.25 per cent this year to 2.75 per cent in 2022-23 and then on to 3.0 per cent and 3.25 per cent in the following years.

Sluggish wages growth has been a persistent problem in advanced economies since the 2008 financial crisis. In the US, wages didn’t really get moving again until unemployment dropped to near 3 per cent.

Perhaps an analogous thing will happen in Australia, or perhaps it might require a terminating unemployment rate lower than the forecast 4.25 per cent.

We need an economic engine

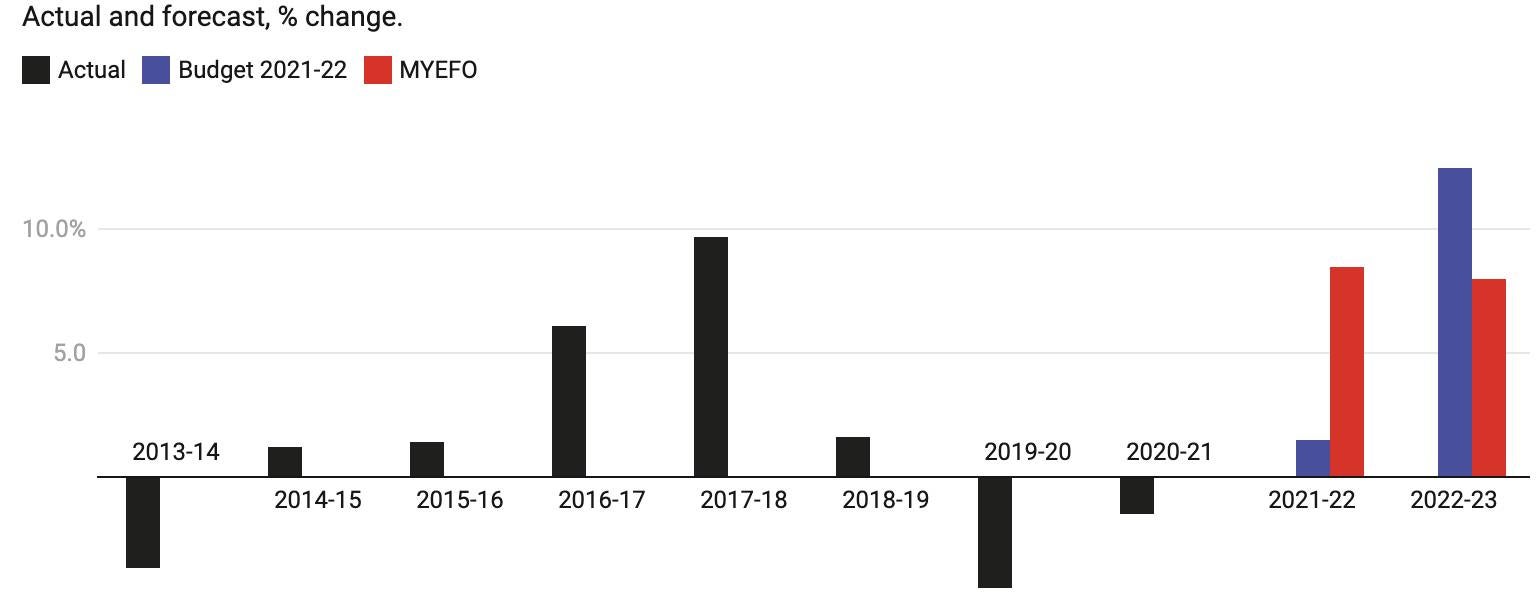

Of course, economic and employment growth doesn’t just happen. They are driven, in no small part, by business investment.

As the following chart shows, this is forecast to bounce back strongly after a big drop during the pandemic. In part, this simply reflects that kind of catch-up, but it also follows from an increase in business confidence. Non-mining business investment, expected to grow 1.5 per cent this financial year at budget time, is now expected to climb 8.5 per cent.

Growth in non-mining business investment

What is now absolutely beyond doubt is that confidence is fragile and depends on support from the government.

The old days of the 1980s, when it was seriously argued that government spending “crowds out” or frightens away rugged capitalists, are long behind us.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s MYEFO statement makes clear there will be no return to austerity, no return (probably ever) to getting back in the black for its own sake.

The massive financial force used during the pandemic worked.

Read more: Why news on wages points to anything but hyperinflation

Government has to keep doing the heavy lifting

In due course, the budget will need to return to something closer to balance. But there is no case whatsoever for a sharp U-turn – not one that Frydenberg and Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy would countenance. Team Frydenberg-Kennedy have prevailed over the Coalition budget hawks.

There are plenty on both the Coalition front and backbenches who still think the Liberal Party is the party of thrift. If that was ever true or sensible, it isn’t now. One might think that Herbert Hoover’s disastrous austerity in the United States in the early 1930s proved the folly of that approach. Or the UK’s version following the 2008 financial crisis.

But, in any case, the dominant forces in the Coalition seem to have learnt their economic lesson. As they say in the classics: “however you get there… ”

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, director of the Economics of Education Knowledge Hub @UNSWBusiness, co-director of the New Economic Policy Initiative, and President-elect of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. His research expertise includes contract theory, law and economics, and political economy. A version of this post first appeared on The Conversation.