Australia's unemployment rate hits decade low amid lockdown gloom

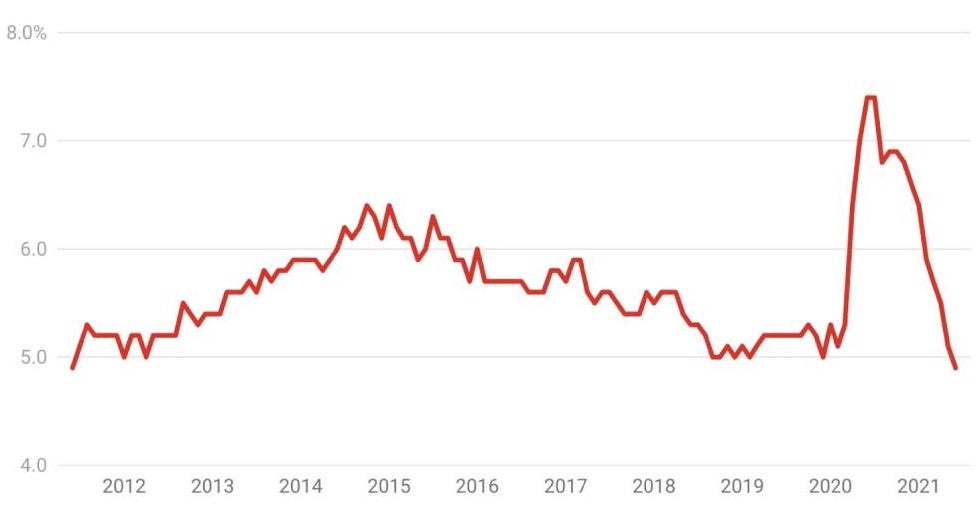

Australia’s unemployment rate has fallen below 5 per cent for the first time in a decade, but it's not time to celebrate just yet, writes UNSW Business School's Richard Holden

In other circumstances, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg might be dancing a jig.

But the pall of the Greater Sydney lockdown, which has now spilled over to Melbourne declaring its fifth lockdown, meant there was no room for smiling yesterday about the latest jobs figures, showing Australia’s unemployment rate in June fell below 5 per cent for the first time in a decade.

The labour force survey data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics shows 22,000 fewer Australians were unemployed last month compared to May. This pushed the unemployment rate down to an eye-catching (if not eye-popping) 4.9 per cent.

Next month’s figures, of course, are unlikely to be so rosy. But these numbers still enable us to understand the progress the Australian economy is making with several important issues predating the COVID crisis.

Importantly, the lower unemployment rate wasn’t due to reduced labour-force participation – sometimes known as the “giving up effect”, when folks stop looking for work because they don’t expect to find a job. The participation rate was steady at 66.2 per cent. In fact, the number of employed persons increased by 29,100 to 13,154,200.

There was even good news for younger Australians, with the youth unemployment rate down by 0.5 percentage points to 10.2 per cent. This reflected a strong recovery from the pandemic, being 6.1 percentage points lower than a year ago in June 2020.

4.9% jobless rate lowest in a decade

Total hours worked

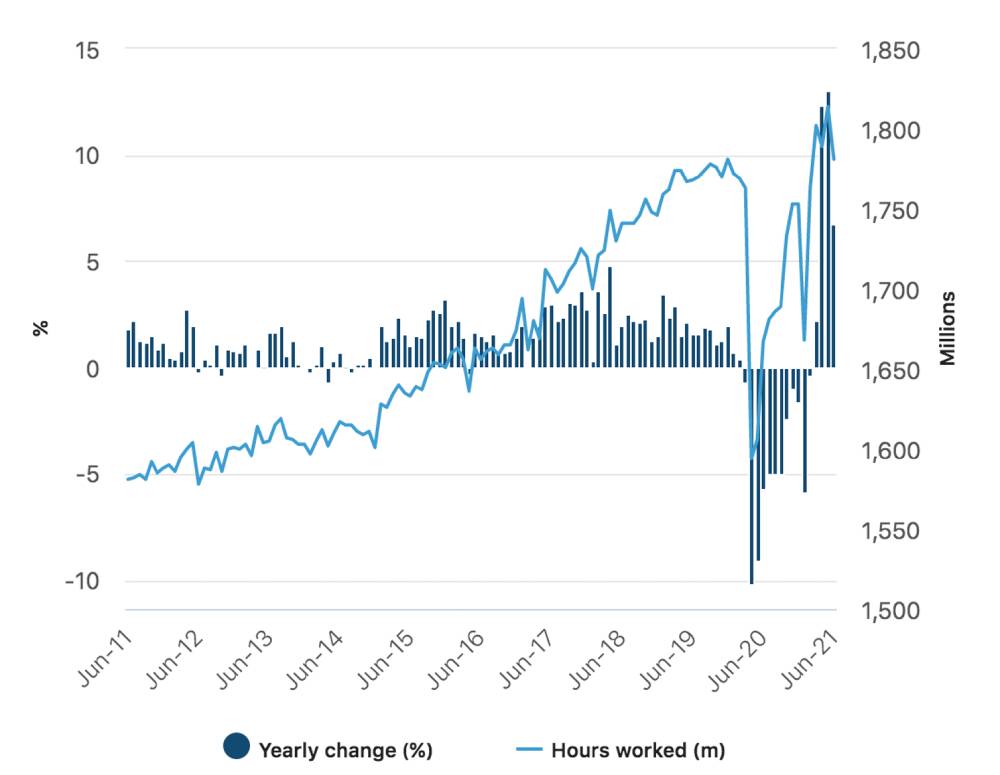

The one statistic I always focus on is the total hours worked number. This is because the headline unemployment rate, as critics always point out, doesn’t tell us to what extent people are getting enough work.

On this measure, there was slightly less good news. Total hours worked in June were down 1.8 per cent, by 33.4 million hours to 1,781 million hours, and that’s seasonally adjusted, so it's not just some “winter” thing.

Monthly hours worked in all jobs, seasonally adjusted

Slow wages growth

In 2019 one could best characterise the Australian economy as barely growing in per-capita terms. Wages growth was stubbornly low, while unemployment and underemployment were unacceptably high.

Having recognised this – too late, mind you, but at least eventually – the Reserve Bank cut interest rates from 1.50 per cent to 0.75 per cent to get wages up, unemployment down, and inflation back into the central bank’s 2-3 per cent target zone. Inflation has been outside its target band for the entirety of Philip Lowe’s governorship, which began in September 2016.

The pandemic pushed the RBA to drive the cash rate close to zero and buy government bonds to push down longer-term interest rates.

Looking at where unemployment, underemployment and wages growth stand relative to 2019 levels, we learn something about Australia’s pandemic recovery. In doing so, we should not lose sight of the economy in general – and the labour market in particular – were not in good shape pre-COVID, and policies to address those issues have long been needed.

Read more: Why has growth slowed globally? It has something to do with technology

Edging closer to where we need to be

So, how’s that going? In some sense, pretty well.

June’s 4.9 per cent unemployment rate is the lowest since June 2011. So getting down to something with a “4” in front of it edges Australia closer to reducing the slack in the labour market sufficiently to push wages up.

But the task is certainly not complete. The RBA's aggressive monetary policy and the “Frydenberg pivot” to aggressive fiscal policy at this year’s federal budget aim to reduce unemployment and hence increase wages.

However, no one really knows how low unemployment needs to get in Australia to getting wages moving again in earnest. The RBA’s official position is maybe 4.5 per cent. Lowe has said it may well be a fair bit lower.

The smart path, arguably, is “let’s find out” – the central bank should keep using monetary policy, and the treasury keep using fiscal policy until we see real wages growth at a sustained level. My own guess is that means getting the unemployment rate down to just below 4 per cent.

Reigniting an immigration debate

The backdrop for these improvements in the labour market is a closed international border. This is likely to become a hot debate – especially since Lowe fired the starter pistol last week by suggesting Australia’s historically high levels of immigration had been helping keep wages low.

Those were rather careless, or at least ill-advised, remarks from the central bank governor, contrary to solid academic evidence pointing the other way.

Read more: Why an ongoing unemployment rate of 5.5 per cent is intolerable

He may say more on this at a future date – perhaps after some discussion and reflection. But, as he is so fond of saying, “only time will tell”.

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School, director of the Economics of Education Knowledge Hub @UNSWBusiness, co-director of the New Economic Policy Initiative, and President-elect of the Academy of the Social Sciences in Australia. His research expertise includes contract theory, law and economics, and political economy. A version of this post first appeared on The Conversation.