Australia's recovery hinges on government spending and vaccine rollout

Australia's economic recovery from COVID-19 depends on government spending and how quickly we get the vaccine, writes UNSW Business School's Richard Holden

We heard an unusual amount from the Reserve Bank last week. On Tuesday, after its first board meeting for the year, the bank outlined plans to spend another $100 billion it didn’t have (“created money”), to buy government bonds in order to keep interest rates down – so-called quantitative easing.

On Wednesday Governor Philip Lowe said he expected to keep the closely-watched inter-bank cash rate at its present all-time low of 0.10 per cent for at least another three years.

And on Friday, Lowe gave evidence to the parliament’s economics committee in Canberra while in Sydney bank staff release updated forecasts. Lowe told the press club that while Australia had a long way to go with its recovery, its economy had bounced back earlier and stronger than he expected. He identified two key reasons. One was Australia’s success in containing the virus.

"As is increasingly clear from our experience in Australia and the experience elsewhere around the world, the health of the population and the health of the economy are linked," said Lowe.

The second was spending by Australian governments amounting to 15 per cent of GDP. "It has provided a welcome boost to incomes and jobs and helped front-load the recovery by creating incentives for people to bring forward spending," he said.

But there’s no necessary reason to assume these successes will continue. Lowe is optimistic about household spending while acknowledging that over the next six months household income is likely to decline as JobKeeper and the JobSeeker extension unwind.

“Normally when income falls, so does consumption,” he said, before adding “we are not in normal times. The extra savings over the past six months and the bigger financial buffers can support future spending – people will have more freedom to spend as restrictions are eased and be more willing to spend as uncertainty recedes," he said.

I’m not as sure.

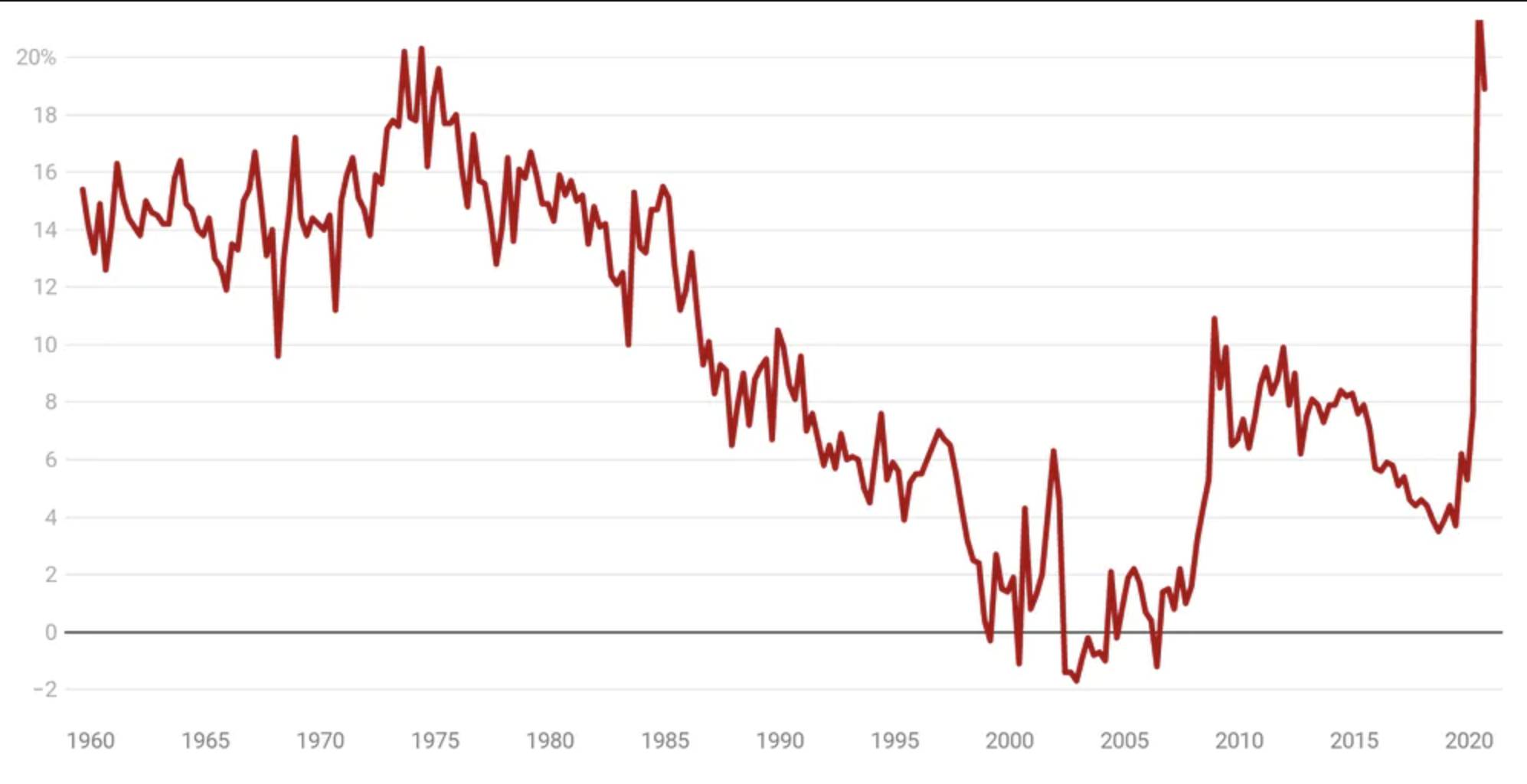

Household saving ratio

ABS Australian National Accounts

Australian households have indeed been saving an unprecedented proportion of their income, but will they really unwind this and the process of repairing their balance sheets at a time when the global pandemic is far from over and it's anyone’s guess when the next one comes.

Health risks aplenty

On the health front, there are reasons to be concerned about Australia’s vaccine rollout strategy, as Steven Hamilton and I outlined last week. More than 100 million people in 77 countries have already been vaccinated. But none here, not until later this month.

Last Thursday the prime minister announced that Australia had secured an extra 10 million doses of the Pfizer vaccine, taking the total to 20 million, to which will be added 53.8 million doses of the Oxford University/AstraZeneca vaccine and 51 million doses of the Novavax vaccine.

But to start with the rollout will be slow – only 80,000 Pfizer doses per week. A slow rollout means a slow recovery. The bank is forecasting an unemployment rate not much better than the one we’ve got by the end of the year.

Economic risks continue

One thing the governor clarified in his address to the press is was his commitment to the present inflation-targeting regime that aims to keep consumer price inflation between 2 per cent and 3 per cent on average over time. Economists Warwick McKibbin, John Quiggin and I have argued that the bank should instead target growth in nominal gross domestic product, which is easier to identify than inflation and more directly impacts living standards.

Richard Holden is a Professor of Economics at UNSW Business School. A version of this article first appeared on The Conversation.