Australia's ageing population: why the reality of the intergenerational report may be worse

With an ageing population and slowing productivity growth, CEPAR's Rafal Chomik says a lot would need to go right to meet projections in the latest intergenerational report

We’ve had five intergenerational reports now, the first (IGR02) in 2002, and the most recent (IGR21) was released on Monday, 28 June. Each has presented a startling picture of a widening gap between the revenue collected from a declining share of predominantly younger taxpayers and the spending needed on an increasingly older population.

In all but the latest, the financial challenge has improved over time. It has worsened this time because the temporary halt to immigration has, for the moment, removed one of the tools we have used to slow population ageing and because the COVID crisis meant less economic growth, less growth in tax revenue, and more government spending than we had been expecting.

What’s sobering

Over the next 40 years, the economy and incomes are expected to grow more slowly than in the past, leaving the budget in continual deficit. This is partly because while spending on ageing and health will increase as previously projected, income from taxes will increase only up to a self-imposed cap, reaching it in the 2030s.

But the reality may be worse. The report is optimistic about migration's rebound, increases in labour force participation, and average productivity growth. But if any one of these generous assumptions doesn’t come to pass, it will be more difficult than projected to balance the budget as the population ages.

What’s probable

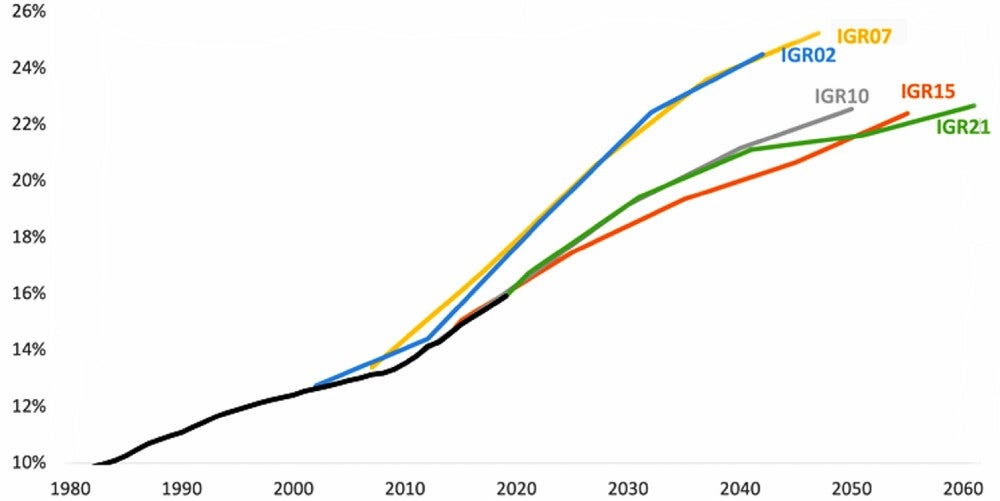

While the demographic fallout from the pandemic is expected to exacerbate population ageing trends, over successive intergenerational reports until now, projections for the proportion of the population aged over 65 have become less pronounced.

Even now, projections for the proportion of the population aged over 65 are tracking those in the 2010 report but haven’t taken us as far back as the first. Much will depend on net migration. It is assumed to rebound to 235,000 people per year by 2025, with a revamped focus on skilled migrants. If it gets and stays that high or climbs, our population will age slowly.

Proportion of population over 65, actual (black) and projected

What’s possible

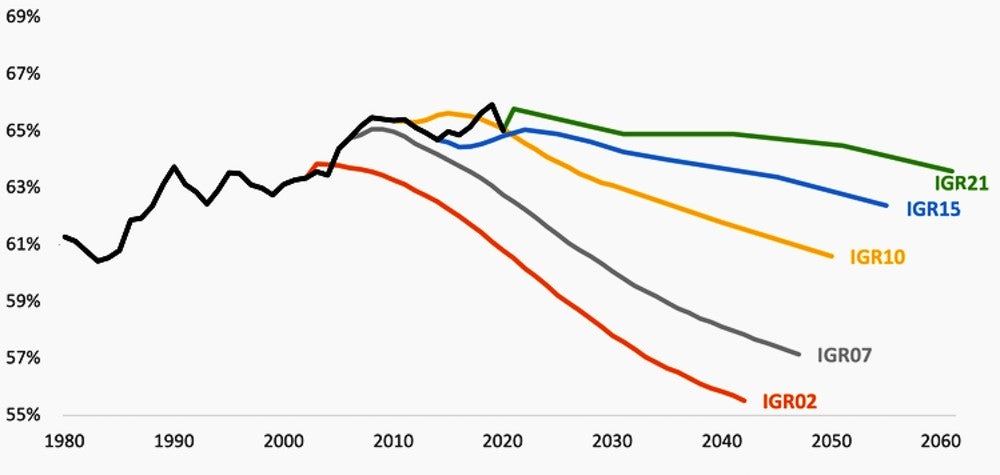

In each intergenerational report so far, a greater proportion of the population has been making itself available for paid work than previously expected. Since 2002, the labour force has grown by 41 per cent. Nearly half of that increase was workers over the age of 50.

There are now a million more women over 50 in the labour force than at the time of the first intergenerational report, and the participation rate of women aged 60-64 had doubled. But increases in older-age participation are slowing even though each new cohort of older Australians is healthier, more educated, and more employable.

Research shows that if older people are to thrive and prosper in the labour market, as the treasury’s figures suggest, Australia will need to dismantle barriers related to health, training, discrimination, work conditions, and scale-up strategies to help employers recruit retain older workers.

Proportion of people aged 15+ in the labour force, actual and projected

What looks over-optimistic

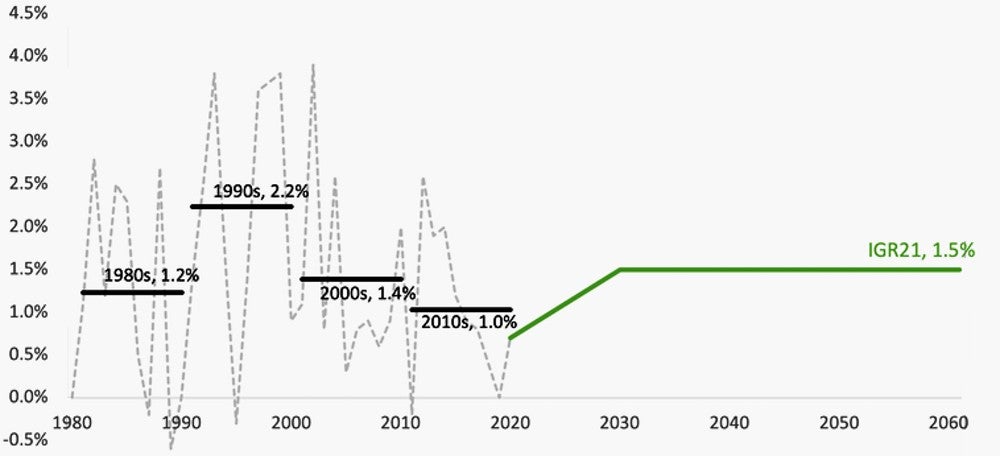

At the launch of the report, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg quoted economist Paul Krugman that “productivity isn’t everything, but in the long run, it’s almost everything.”

With greater labour productivity (GDP per hour worked), we earn more with the same or less effort, potentially offsetting the economic and fiscal impacts of ageing. The report’s productivity growth assumption for the next 40 years is based on the average of the last 30 years: 1.5 per cent per year.

Yet recent rates have been much less and have been declining over time.

Labour productivity annual growth and decade averages, actual and projected

Average annual productivity growth over the last decade, including the pandemic recession, has been 1 per cent. Treasury’s sensitivity modelling shows that lower than projected productivity growth of 1.2 per cent would see the economy and incomes 9-10 per cent lower by 2060-61 and the budget deficit 2.2 percentage points wider.

Australia isn’t alone in experiencing a slowdown in productivity growth, and it isn’t clear how much Australia by itself can do about it. The report points to a suite of microeconomic reforms related to competition, digital technologies, patents, research and development, and skills, some of which were recommended in a landmark review by the Productivity Commission in 2017.

But as the treasurer pointed out, many of the big reforms have already been done. As he put it: “you can’t float the dollar twice”.

What’s unmodelled

And a key set of figures are missing from the report — those relating to the impact of climate change. There is a chapter on the environment describing risks, but it doesn’t feed them into formal projections in the way this month’s NSW intergenerational report did.

Frydenberg’s report is commendable. It presents an opportunity to talk about ways to achieve a better future – not just the one it outlines.

Rafal Chomik is a Senior Research Fellow at the ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR), located at UNSW Business School. He specialises in social policy design, public and private pension analysis, static microsimulation modelling of the tax-benefit system, and poverty and income measurement. A version of this post first appeared on The Conversation.