Digital activism: how social media fuelled the Bersih movement

While social media played a key role in empowering the masses in Malaysia's Bersih movement, it still took some form of organisation and formalisation to sustain the global social movement

The last few years gave rise to several social media-driven civil movements, notably Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion, which have continued to advocate for social and political reform. As more people turned to social media for news and information, and consumers demanded that companies stood up for critical issues such as the fight against climate change, businesses also became increasingly active on social media. But how exactly did a group of activists with a shared vision sustain a large global social movement?

History provides some examples of how to transform connection into collective action, according to Dr Carmen Leong, Senior Lecturer at UNSW Business School. An analysis of the Bersih movement, for instance, illustrates the mechanisms required to mobilise people to effect social change. A recent study, Digital Organizing of a Global Social Movement: From connective to collective action, examined how platforms like Facebook and YouTube were utilised by the Bersih movement to mobilise people worldwide for several years. The paper was co-authored by UNSW Business School's Dr Leong and Senior Lecturer Dr Felix Tan in collaboration with Barney Tan, Associate Professor at the University of Sydney, Isam Faik, Assistant Professor at Ivey Business School, and Khoo Ying Hooi, Head and Senior Lecturer at the University of Malaya.

Why Malaysia’s Bersih movement?

In Malaysia, the Bersih (or “clean” in Malay) was a civil movement consisting of 84 non-government organisations that called for reform of the country’s electoral process to be free, clean and fair. Bersih was first launched in November 2006 with opposition political leaders and representatives from civil society. In 2007, Malaysians took to the street to call for reform, but police refused to issue a permit for the rally rendering it illegal, and protestors were met with tear gas and chemical-laced water cannons. By April 2010, the movement was re-named Bersih 2.0 – a wholly non-partisan movement free from political influences. Following these demonstrations, the government set up a Parliamentary Select Committee to respond to the electoral issues, which released a report with 22 recommendations to improve the electoral system.

The Bersih, however, was unsatisfied with the recommendations. The existing election commission was tasked to carry out the recommendations with lengthy implementation periods, which failed to mention many of the allegations of electoral fraud. In light of these issues, the third public demonstration – the Bersih 3.0 rally – took place in 2012. Despite being a peaceful demonstration, protestors were once again met with tear gas and water cannons. In total, four big rallies took place in 2007, 2010, 2012 and 2015. The size of these rallies grew from 30,000 in 2007 to 200,000 by 2015.

Speaking on the motivations for her study, Dr Leong said she was interested in finding out how social media could enable and sustain the movement, and Bersih proved an excellent case study. Also, as a Malaysian herself, the issues behind the movement were close to her heart. “As an information systems scholar, this phenomenon in which social media enables people to come together interests me, especially people who are overseas,” she said.

Indeed, the ‘Global Bersih’ was a movement coined by Malaysians living overseas to support Bersih and its cause. In conjunction with the Bersih 2.0 rally, Global Bersih organised rallies in 38 international locations with 4,003 overseas Malaysians in solidarity.

Dr Leong explained: “Bersih was the biggest movement in the country itself, and it sustained for years, unlike the other social movements. It is even more fascinating to us to realise that the global Bersih movements (which were joined mainly by Malaysian overseas) were driven by a small group of people leveraging social media and technological means.”

How cooperation sustained the Bersih movement

To find how the connective action of social media-based movements developed into more organised, concerted forms of collective action, the authors collected data from interviews and social media logs and news, reports, books, and magazines that covered the Bersih movement. Data from social media, including Facebook and YouTube, were reviewed to generate a contextual understanding of what transpired as the Bersih movement unfolded. Their findings revealed the movement was sustained for so many years because those leading it developed structured forms of organising, which eventually led to the establishment of a relatively stable network of activist groups.

“The first finding was the dual effect of social media and in our research the dual effect on the growth of social movements. On the one hand, they offer movement activists a heightened ability to direct the public’s attention to their cause, evade censorship, and mobilise at a large scale.

“On the other hand, the rapid scaling of social media-enabled movements limits their ability to build a capacity for sustained mobilisation, which often comes from personal interactions in the long process of coordinating sequences of movement actions and counter-actions. Organisations and individuals using social media for organising must realise the dual effect,” said Dr Leong.

Studies of traditional social movements have long discussed the shift of movements towards increased formalisation as a common phase in the evolution of movements. However, until now, limited attention had been given to understanding the shift in movements built around social media platforms, explained Dr Leong.

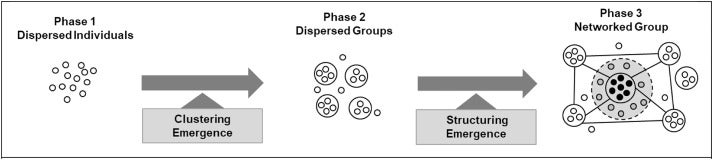

So, although social media empower movements, in the long run, it can also disempower them. Understanding this paradox requires attention to both the clustering and structuring emergence of social media-enabled movements – the two phases of growth required to sustain a movement, reiterated Dr Leong. Mobilisation happened in part thanks to the shift towards more structured forms of organising, and the critical phases can be viewed in the chart below:

What social media-enabled mechanisms shape the emergence of a global social movement

In the paper, the authors concluded that given successful collective action requires formalisation and standardisation of the movement’s activities, advocacy-oriented actors in civil society need to focus their energies on cooperation to be successful.

Practical implications

Speaking on what was most surprising about the findings, Dr Leong said: “While we knew from our own networks/social media groups that we join that Malaysian diaspora was supporting the movement from overseas, we did not expect that the Global Bersih was driven by a small group of organisers. In fact, all of them have never met each other in person,” she said.

“From the small, dispersed groups of people who connected themselves via social media, a semi-formal structure emerged. People started to organise themselves in a more formal hierarchy. Based on their expertise, they found themselves a ‘position’ in the structure.”

What did this look like in practice? A journalist, for example, would become in charge of social media accounts, and there was also a semi-formal group of city coordinators whose names were collated for activation when a global rally took place. All of these loosely connected groups of people maintained their network on social media.

Resources such as time and human capital are indispensable in sustaining and ensuring the effectiveness of collective activism. Still, a structure and organisation that garner supports from various sources are ultimately critical.

“Activism often involves a cause to address a social defect that is difficult to address and overcome in a short period. Still, unless there is a dedicated team or organisations, it would be hard for any single person or small groups of people to sustain the activism”, added Dr Leong.

But with growing concern over how social media may be an echo chamber, used to propagate fake news or specific messages, Dr Leong concluded that it was important to consider how this has affected the diversity of activists voices.

Dr Carmen Leong is a Senior Lecturer at UNSW Business School and her research interests include digitally-enabled strategic transformation in organisations and digital empowerment in social studies. Dr Felix Tan is a Senior Lecturer at UNSW Busines School and the founder of UNSW UNOVA, which helps organisations navigate the process of digital transformation through research and development. Dr Tan's interests include digital platforms and ecosystems, enterprise systems and digital transformation.